Text: Silvia Cruz Lapeña

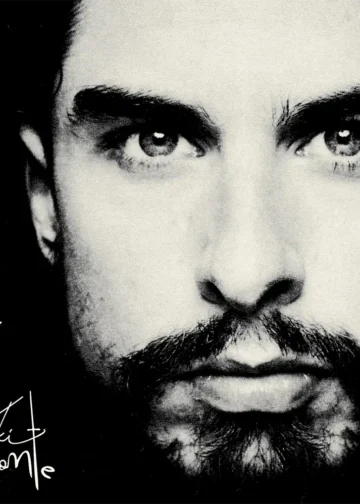

Photos: Remedios Malvarez / Paco Barroso (b/n)

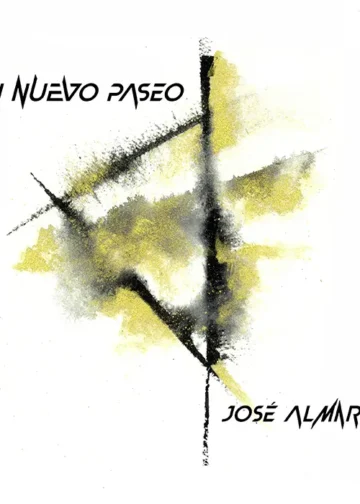

The singer-composer from Triana debuts her third album, «Delirium Tremens»

“Flamenco is a long-term career, you can’t say someone has caused a revolution after just two or three recordings”.

In a round of short questions and fast answers, there’s only one Rosario “La Tremendita” doesn’t answer in a flash: Is the flamenco fan more demanding than followers of other kinds of music? “Hard question” she says, and that’s enough of an answer. At this point in the interview, she tells us that her main fear is loosing herself, the words she uses the most are “fear” and “freedom”, pure contrast, and that she would like to have a better memory than she has, because she forgets everything.

Of her material possessions, she would only save her instruments, which reminds us that she’s not only a singer, but also a musician, composer and lyricist. Her performance singing and playing the electric bass in Andrés Marín’s latest show, “Don Quixote”, is a good example of her active mind. And so is Delirium Tremens, her third record after A Tiempo and Fatum. She believes that flamenco people read little, and when you ask her to name a book, she talks about the Complete Poetry of Anne Sexton (Linteo, 2013), distancing herself from the most time-worn verses and styles of flamenco.

Grateful

“In art, it’s harder to lie, and you create such a personal work, it’s very complicated to hide my feelings”. Rosario realizes that Delirium Tremens is an outright confession. There’s nothing superficial on the record, but rather emotional states and above all, the reflection of emotional phases the singer has gone through and which she describes as “a personal crisis that lasted almost four years”.

Those stops along the way, divide the record into four parts: chaos, escape, learning and gratitude. “It wasn’t always clear that I was going to reach the last stage, I didn’t think I would be able to be thankful for negative things that happened to me all at once, but that’s how it was”, says the now upbeat singer, having overcome her bad run.

In Delirium Tremens she’s influenced by Anne Sexton, but also by José Ángel Valente, and it shows in the themes and in the tone, but most of the verses are her own. “There are also popular verses, and two gifts: one written by Carlos Marquerie, ‘my hell is your heaven’, and another by Rocío Molina, ‘lava softens straw’, a sort of tongue-twister very much in her line that says nothing, at the same time saying everything, which is why each individual has to find their own interpretation.

Liberated

Three years ago in this magazine the singer from Triana confessed she was living through a phrase in which she thought she should “prove herself less, and enjoy more”, but now she realizes that that wasn’t exactly right. “I still keep the part about enjoyment, raised to the maximum. However, at that time I used to say that phrase to see if I could believe it and make it come true, but it didn’t work. Now yes, now I’ve reached that stage”.

On the new record there’s rumba, serrana, bulerías, zambra, mining songs and abandolao, romance and soleá de Triana, but don’t look for classic forms in the usual sense because “La Tremendita” has gone in for a more contemporary sound that features trombones, her electric guitar, the piano and drums. “It’s an experimental work, but with very traditional roots, because both those elements are absolutely necessary for me”.

Pianist Abe Rábade and bassist Pablo Martín Caminero have helped her achieve that with their arrangements, the latter being responsible for the record ending with sevillanas. “Pablo made me see that ‘Delirium Tremens’ was a circle, and that the recording had four parts, just like sevillanas, and that it would be a good thing to end like that”, she says in reference to the piece she sings with Estrella Morente. “I didn’t think our voices would go so well together, but the fact is it all worked from the first moment”, she says about the last cut on a record made in one single day. “Another sign that there was no fakery” she says firmly.

A new generation

Rosario says she feels liberated, that these years of thinking and searching for the way she wants to do things have been fruitful. “I began at five singing in peñas, and it’s been very hard to break away from that and make my way” she says, although she claims she’d have no problem singing in a peña again, because that’s where she learned so much about flamenco singing, discipline and responsibility.

She speaks with bravado and energy this woman who claims to have no aim of revolutionizing flamenco. She believes the term is abused. “There’s a generation that’s doing different things, we’re brave and we have something to say, but flamenco is a long-term career, and you can’t say someone has caused a revolution after just two or three recordings”. She cites the case of Enrique Morente as an example of what was a before and an after, and adds that “to talk about change and real contributions, there has to be a long career, and many years have to pass to determine what an artist has contributed”.

Now, the distribution of her record is handled by Universal, but she’s the one who records, listens to herself, gets the musicians, the inspiration and also the financing. “Sometimes I feel like I’m the one supporting the art-form” she says devilishly but laughing, far from any bitterness.