Text:Silvia Cruz Lapeña

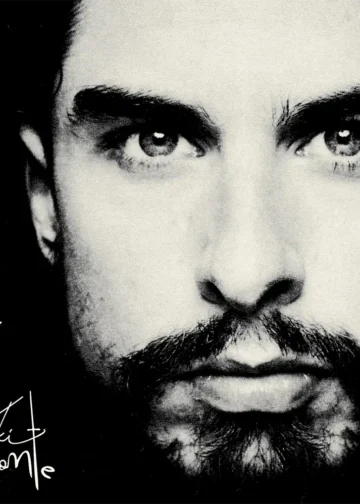

Photos: Jean Louis Duzert

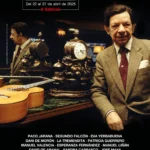

The Seville dancer presents his interpretation of the Cervantes character at the Nimes Flamenco Festival.

Dance: Andrés Marín, Patricia Guerrero, Abel Harana

Drums and percussion – Daniel Suárez

Voice and electric bass: Rosario La Tremendita

Cello: Sancho Almendral

Electric guitar: Jorge Rubiales Tiorba

Skateboard, cement, cross-dressing and nudity are just a few of the many elements that dancer Andrés Marín makes use of to create his “Don Quixote”. The work, which debuted in November at the Paris Biennale d’Art Flamenco, is the fruit of an artistic residence at the Chaillot Theater, and opened the 2018 Nimes festival.

The work is not a recreation of the novel by Miguel de Cervantes, but a very personal vision of the noble man of La Mancha through which the dancer seems to exorcise demons of his own. “No soy” (I am not), says the sign above the stage. “I’m not anyone’s knight” sings Rosario la Tremendita as a martinete, and in that short phrase the key to Marín’s work seems to exist, a work that was danced as in recent times: short movements and exploiting his interpretive facet almost more than dancing.

The entire work is designed to make an impression, also the stage design created by Laurent Berger, although some ideas worked better than others. For example, making this Quijote urban is a feat. To achieve it, there are no Castillian fields, no windmills, no inns on stage, but skating rinks and screens that broadcast non-stop announcements. The horse Rocinante is substituted by an electric skateboard and where it all takes place, is very dark, so much so at times that it’s impossible to distinguish movement and details.

A ten for Tremendita

More than an adventure novel, the setting seems conceived for tragedy, perhaps one of Shakespeare’s, maybe Macbeth, but in its Japanese version. Because the fact is, there are moments, especially at the beginning, when Marín reminds you of Toshiro Mifune in Trono de Sangre, a film of Akira Kurasawa, and it’s delightful. In those brief movements, almost like a marionette, meticulously measured and eloquent, is where Marín concentrates everything he already knows and is familiar with, which is why each gesture seems to hold an entire world.

That Shakespearian touch can also be seen in the role of La Tremendita, a kind of sorceress who invokes everything, and who is, without a doubt, a perfect fit for this work. The Triana singer not only plays the electric bass, dances and guides her companions, but sings lying flat on a skateboard without missing a note. She gets a “10”, for her voice and for her presence, absolutely powerful for the two-hour duration of the show.

The music is another strong point. The cello, thiorba and electric guitar contribute very opportune strings for a very intense work, but overall it’s the percussion that takes the cake. Daniel Suárez is in charge of a monumental work with which he accompanies footwork done with sneakers and the decisive moments of the entire composition. That’s what a percussionist should be, a magician in the shadows, and if interest doesn’t flag more often, it’s thanks to his work.

A femme fatale Dulcinea

Something Marín doesn’t forget is humor, which is key to Don Quixote. The poet Luis Rosales once compared the Cervantes character to Charles Chaplin because “just like him, he starts out as a clown, and ends up becoming a miracle”. That point is achieved by the dancer in some of his interpretations, and he takes advantage of Sancho Panza, dancer Abel Harana, for the most comic scenes. For example, when he gets him marking bulerías atop a skateboard, or makes him dance inside a sleeping bag.

Less effective is the play of mirrors that represent Quijote. Professor Francisco Rico, perhaps the leading expert in that novel and its central figure, explained in one of his lectures that Cervantes constructs his character making him travel from Alonso Quijano to Don Quijote, taking him from madness to sanity, from nonsense to boredom. In that sense, Marín gives no rest to his Quijote. His knight lives immersed in another world, he barely unfolds it, or doesn’t realize.

Another strong point is Dulcinea. She’s played by Patricia Guerrero, the most flamenco character of the work, it makes no difference if she dresses as a football-player, a boxer or a character from the movie Matrix, because she dances everything with her body and with her mind. We see her in an effort of tangos and even in a sort of minuet with Marín. Guerrero dances intelligently, you can even see it in the bend of her wrist. There are no unimportant steps for her, no battles, everything is war. It’s the kind of energy that reaches the spectator even without understanding, whether sleeping or watching the show from the last row.

Somewhat forced

“Don Quixote” is plagued with details and references that could be interpreted in many ways. One possible interpretation, perhaps off-base or perhaps not the only one, is that this is the story of a creator fed up with being called crazy or not being understood. The story of someone who has decided not to defend himself any more. Marín seems to say “I’m not anyone’s knight” with a show where he is who he is, who he wants to be, not who others want him to be.

But his defense gets up on the stage, the audience sees it. And the people of Nimes had a hard time getting the message, although they applauded at the end. The work has moments full of ingenuity, originality and strength (the dancer-boxers for example), and ought to emphasize them more. However, you have the feeling Marín, creator and author, is the one who stands out the least. And also that there are too many elements in the work, some overly contrived. “The fascination the Quijote produces, with the silhouette of Cervantes in the diffused light, is always radically implausible, and always absolutely natural”. Thus summarizes Rico the power of attraction of the character. Marín’s is also unreal, fabulous and incredible, but only in certain moments does it feel natural.