|

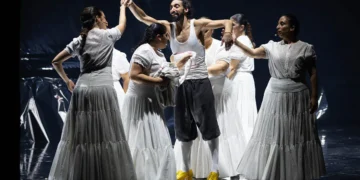

Dance: Juan Manuel Fernández ‘Farruquito’,

Antonio Fernández ‘Farruco’, Pilar Montoya ‘La

Faraona’, Juan Montoya ‘Barullo’, Antonio Moreno

‘Polito’, Adela Campallo, Keren Jacobi ‘La Hachara’.

Cante: Montse Cortés, Encarna Anillo, José

Valencia, El Canastero, Antonio Zúñiga. Guitar:

Román Vicenti, El Perla. Artista Invitado:

Manuel Molina

And on the seventh day we rested. Thursday the only show

on the festival program was at the Villamarta Theater, but the magnitude

of the individual at the top of the bill made this day the most

anticipated of the entire festival.

But first things first… At the morning press conference the work

“Inmigración” was presented by its author, Fernando

González-Caballos who explained that it is directed to those

foreigners who dream of embarking on a career in flamenco, and pointed

out that Miguel Poveda, the singer who shares the bill with “Inmigración”,

is an immigrant himself. Producer José Carlos Lérida

commented on the social commitment and the need to avoid superficiality,

adding that the show generated more expense than income.

is the festival’s most important draw. Ever since the child

prodigy came of age he’s been surprising audiences the world

over as well as in Spain with his dynamic and original dance which

is, at the same time, rigurously traditional. Manuel Molina opens

the presentation relating the family saga of the Farrucos and sings

a verse which years ago was recorded by the Familia Montoya: “Vamos

a bailar como los gitanos, con luz y color” [‘Let’s

dance like the gypsies, with light and color’], and the line

couldn’t have been more appropriate.

The group is hot. Who says fandango de Huelva isn’t a gitano

dance? With Farruquito and his people this form, usually inoffensive,

turns into a lethal weapon and makes an apt presentation in which

no energy is spared. The audience goes wild with the appearance

of each member of the family, and everyone tries to sort out which

one is which, shouting and applauding with insatiable hunger to

see these astonishing young people.

The show has grown and matured a great deal since its debut in

Mont-de-Marsan last June. Manuel Molina has a bigger role and the

two female dancers, a smaller one, and both changes are positive

in terms of the overall effect. The farruca which Román Vicenti

plays with alternate tuning sounds excellent, but this dance of

Farruquito’s is perhaps the weakest part of the show, no doubt

because it depends more on theatrical movements than on the compás

the dancer manages with such authority, and the red velvet suit

he wears might be what prompted one London critic to call Farruquito

“Spain’s Michael Jackson”.

This isn’t watching dance…it’s

nourishment!…we’re

putting on weight with every passing second.

But as always happens with great artists, Farruquito makes us his

accomplices, we never tire of waiting for his flashes of genius

and absolutely everything is forgiven. The level of his brother

Farruco’s dancing continues to go higher and higher and the

people sitting next to me commented that he has surpassed Farruquito.

But no, the integrity and maturity of the elder dancer, his presence

and his willingness to take risks are qualities not yet matched

in the younger brother.

Among journalists we remark on the difficulty of finding words

to describe the indescribable, when long ago we already ran out

of appropriate adjectives. The rhythmic applause is not reserved

for the end but springs up again and again from the culturally diverse

and totally enthralled audience.

the siguiriya an ingenious touch takes away the collective breath

and provokes a tear here and there. A corpulent figure, possibly

La Faraona dressed in a man’s suit, a hat covering the face,

ascot, cane in hand, slowly crosses the rear of the stage while

Farruquito and friends are raising flamenco hell. It’s old

Farruco! He stops momentarily, glances at the ruckus and continues

on his way. What could have been a corny trick, gives the perfect

touch and reinforces the message of the work: continuity.

This isn’t watching dance…it’s nourishment!…we’re

putting on weight with every passing second, but as happens with

all powerful drugs, instead of becoming satiated, we need more and

more. Manuel Molina provides a sort of epilogue, the fiesta finale

follows, the smallest member of the family comes out to dance, Joselito

Valencia’s cante is to die for, we’re out of breath

and wish it would never end.

Emerging to the world devoid of compás outside the theater

I thought, if the most traditional kind of flamenco, without cajón,

dumbek, nudism, choruses or any other kind of extravagance is capable

of reaching such heights, why aren’t we more demanding? Why

do we settle for the merely pretty when this art, which is bigger

than any artist who practices it, has this perfect and never-ending

built-in dynamic?

Text : Estela

Zatania

|

|

Theater

Villamarta Program

De Peña

en Peña Program: Trasnoches,

De Peñas, Peña de Guardia

Other

shows(Gloria Pura, Bordón

y cuenta nueva, De la Frontera, Café Cantante, Sólos

en Compañía)

Courses

and workshops

Descubre más desde Revista DeFlamenco.com

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.