|

Sala Joaquín Turina. Thursday, 22th november

|

||||||

|

Text: Juan Vergillos Stripping down to basics as easily as breathing Dance: Rocío Molina, Laura Rozalén. Guitar: Paco Cruz, Manuel Cañas. Cante: Jesús Corbacho. Percusión: Sergio Martínez. Palmas: Popi, Vanessa Coloma When grand conceptual pretensions are put aside, be they of others or one’s own, she does her best work; when she digs into her most intimate self, the smallest details. Rocío is growing right before our eyes. She is becoming a woman right on stage. The first time I saw her in the La Unión contest in 2003, she was barely an adolescent. At that time I gladly welcomed her intrusion into the flamenco panorama, and suffered the blindness of the contest’s jury who didn’t even let her pass to the finals. This summer Rocío Molina returned to La Unión as a major star. The lovely contradictions of flamenco.

Rocío has come a long way in just the last year. In two earlier productions, “Entre paredes” and “El Eterno Retorno”, the concept was not up to par. An interpreter with overwhelming technique and plenty of ideas, who nevertheless fell down in the conceptual department with an excess of intellectual baggage that was obviously at odds with the freshness of her dance. Some of these ideas came from others, and this you could tell. Hoping to avoid disaster, a renowned theatrical director was taken on, as well as a renowned actor and a renowned popular singer…there was public money behind the project. But no. Logically, with elements of that caliber, the unavoidable disaster was all the more glaring. Now Rocío has returned to the fold of intimacy. Stripped down. We saw her a few months ago in the show “Por el Decir de la Gente” reviewed in this magazine, in which Rocío eschewed some of the more showy elements of the art, such as the guitar. And also last night in Seville’s Sala Joaquín Turina, with this “Turquesa Como el Limón”, which premiered last year at Madrid’s Pradillo Theater. Rocío tells us about herself, speaks about herself. About herself and her partner Laura Rozalén. The show presents them as two opposite but complementary dancers. Laura is all light, sea breezes, not traditionalism, but traditional forms updated. The bata de cola as dancewear, the “rag”, clothing, not as used by others today with complex technique. That’s not what it’s about, but rather showing off the train as easily as breathing. The style of the principal dancers of the end of the nineteenth century. Macarrona, Malena, Pastora Imperio. In other words, hands, arms, gliding smoothing, a look charged with insinuation. Smiling in alegrías, could there be anything simpler, more necessary and pleasant? And garrotín, a discreet monument, without pretensions. Rocío providing the shadows. In fact there’s one moment when we can barely see her figure. Frenetic dancing, the body’s power unleashed, the torrent, the eloquent sum of it all. So extreme, it leaves you speechless. The ability to dance every sound and every silence. Each idea and sensation. The facility, obviously a result of abundant studio time, for saying exactly what she intends. Saying everything, and saying it well. A prodigy.

There’s also the stage presence (as I said, this girl is becoming a woman right on stage). And the biographical details: Laura speaks from off-stage in what seems to be a journalist’s interview of Rocío. And Rocío dances each one of the words, the syllables, the vowels and consonants with their silences. And then, vice versa. Sky and earth. Tradition and creation. Stillness and frenzy. Receiving and giving. Two necessary and complementary truths, although there is the occasional glitch, some friction. All affection involves friction, as you know. Rocío the actress, receiving the audience dressed as a stewardess, playing the adolescent, which she is, seductress and child. Or as young mistress of this art. With no underpinning of any kind, and all the naturalness of breathing. In many ways she is today’s most important dancer. That’s how it is, don’t ask me why. She’s growing so fast, you have to say she’s 23. Biographic irony. The handicaps we all have to deal with; in Rocío’s case, not very many, whether due to her own willpower, or because the gods smile upon her. Or both. Rocío laughs at her handicaps, at her critics. And at herself, naturally. The end is a pas de deux with bata de cola and castanets, wood that sounds like metal, “Tres Morillas de Jaén”, a popular song, and it wasn’t the only one of the night (there was also bossa nova, lyrical song, bolero, jota…even flamenco), in which the melody was suggested by the guitar and the dancer’s feet, while the human voice opens and closes with trilla. And the fiesta finale is a rip-roaring rumba. Viva life! The closing is an everyday scene, almost quaint, the two girls look at themselves in a mirror, argue over the mirror and play with it. And the mirror is us. The audience. And everything without grinding any axe, as easy as breathing in and out. |

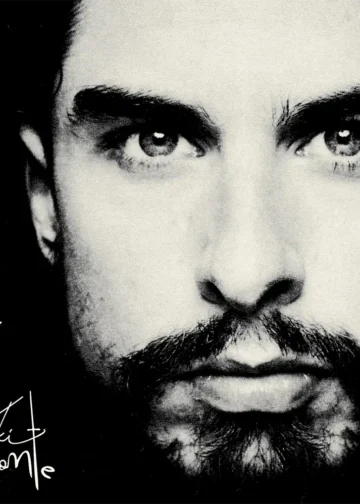

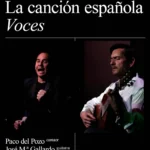

Rocío Molina, Laura Rozalén

Rocío Molina, Laura Rozalén