|

Text & photos: Estela

Zatania

Dance and choreography: Rocío Molina. Guest artists:

Lola Greco, Manolo Monteagudo. Special collaboration: Pasión

Vega. Piano: Rafael Marinelli. Guitar: Juan Recuña, Jesús

Torres. Cante: Antonio Campos, Antonio “El Pulga”. Percussion:

Sergio Martínez. Palmas: Luis Cantarote, Carlos Grilo. Staging:

Pepa Gamboa. Original idea, music: Juan Carlos Romero.

Seated in the lovely Teatro del Carmen in the lovely town of Vélez-Málaga,

thirty kilometers from the capital of the Costa del Sol, while waiting

for the curtain to go up, I read the program notes to discover that

the work I am about to see is based on concepts from Nietzsche,

Borges, Szymborska and Zorn, and seeks to “free us of stereotypes”.

So I pass the time thinking about what a stereotype is, and how

it comes into being. The topic is not entirely devoid of relevance

since an entire generation of flamenco artists has felt the need

to reject what it considers stereotypes, while it’s not entirely

clear how they are to be defined.

Before a stereotype comes into being, there is a truth –

a reality so blatant and undeniable that no divergence of opinion

is possible. In time, successive generations cling to that truth

without questioning it, and “the truth” runs the risk

of becoming deformed since no reality checks are being made. The

art of flamenco is now going through a process of reassessment and

stock-taking in which every one of us, artists, critics and consumers,

are obliged to find our own personal truth, the frontier that separates

that which is worthwhile and valid, from the merely novel, mediocre

or cheap.

That bit of introspection is to the point because Rocío

Molina is an exceptionally gifted and intelligent young dancer who

with “El eterno retorno” which premiered as part of

the Málaga en Flamenco festival, has set her frontier with

imagination and dedication, and now we must pass judgement on the

final result, brutal though that may sound. A quick flashback….

Little more than a year ago, at the prestigious contest of La Unión,

this young lady impressed a lot of people with her very original

style and her sheer ability, but she never made it to the finals.

Just five months later she was touring the US as a star in her own

right with the Festival Flamenco USA that included some of flamenco’s

biggest names such as Sara Baras, Eva Yerbabuena, Enrique Morente,

Tomatito, Gerardo Núñez, Belén Maya and others.

Two months later, at the Festival de Jerez in March of this year

2005, she presented her own small group, dancing alone through a

program of long numbers with equally long batas de cola and such

a high level of performance, the venerable Sala de la Compañía

was rocking with enthusiastic applause, shouting and foot-stomping,

and you went out into the street with that feeling you occasionally

get of having seen something truly important.

In her hands, feet and body is the capacity

to open new paths in women’s flamenco dance

From March to September is six months, and the 21-year-old dancer

has evolved dramatically in this short time. With “El eterno

retorno”, her most important work to date, we see her not

only as a dancer, but as choreographer and interpreter as well.

The central theme of the work, expressed by narrator actor Manolo

Monteagudo, is “all things disappear, and all things return,

everything happens for the first time, everything is relived eternally”,

and a translucent revolving door in the middle of the stage where

performers enter and exit is the graphic representation of those

words.

Molina first appears in a black bata de cola – in this work

her wardrobe is far more becoming than anything she’s worn

before – to dance soleá with the sole accompaniment

of the singer’s voice which highlights the famous Serneta

verse, sung and then recited, “Fui piedra y perdí mi

centro, y me arrojaron a la mar, y a fuerza de mucho tiempo, mi

centro vine a tomar” [‘I was a stone that lost its center

and was thrown into the sea, after trials and tribulations I found

my center once again’], echoing the work’s philosophical

theme. To the sound of a violent rainstorm, Seven musicians arrive

from the rear of the theater, one by one, protected from the “rain”

by the narrator’s umbrella. Pepa Gamboa was in charge of the

staging, and she knows what she’s doing, but you sometimes

have the feeling that flamenco was sacrificed at the altar of theatrical

effect.

Rocío dances a rondeña ending with the free-form

malagueña of Chacón, “Se me apareció

la muerte…”. The voice of Granada singer Antonio Campos

is always a treat, but the compas-less dance doesn’t manage

to avoid the movements of silent-film excess. No problem, the show

is full of clever touches. The friendly narrator comes on again

to entertain us while Rocío, dressed in a vanilla-colored

dress, scatters the stage with “typical Spanish” dolls,

the kind that dance eternally and statically upon many a television

set. What better way to banish stereotypes than to wallow in them.

The guitars strike up with alegrías and the beauty of the

music makes me scramble to consult the program notes to discover

that we have Juan Carlos Romero to thank for these wonderful new

sounds achieved with no other instrument than the guitar. This is

the strongest and best-developed piece of the show. Rocío

lets us glimpse her originality and recalls the movements of a young

Carmen Amaya with angular arms at face level and deep barrel turns,

an aesthetic that harks back to the past, effectively updated by

this dancer. “Cuando te vengas conmigo, a dónde te

voy a llevar, a darte una vueltecita, por la Alhambra de Graná”…

This is an integral work and even the cante verses are a premeditated

part of the whole.

That feeling you occasionally get of

having seen something truly important…

With modern black culottes and white wrist-cuffs, Rocío

dances siguiriyas at a fast clip, as is now the fashion…as used

to be the fashion…and you begin to miss the bata de cola this

dancer manages so expertly. The always fascinating Lola Greco, divine

goddess with extremities whose movements defy the norms of human

anatomy, dances a pas de deux with Molina, and singer Pasión

Vega puts voice to the piano accompaniment. Hold on…Pasión

Vega? Of course…she’s from Málaga! So she had to

be shoehorned-in somehow, but she continues to be a Spanish lyrical

singer despite the Bladerunner hairdo and attire. Are we not, after

all, rejecting stereotypes? But there’s still more…Vega

comes up front for a slow rendition of “Los cuatro muleros”

which with the voices of the cantaores morphs seamlessly into guajira,

alegrías, tangos del Piyayo, tangos, soleá, bulerías,

siguiriyas and tonás, without a blink…the marathon leaves

us breathless and the applause is politely reserved.

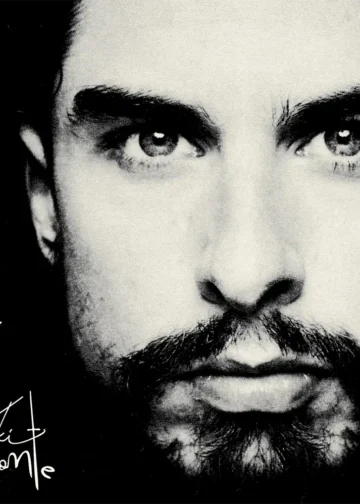

Rocío Molina with Lola Greco

So what’s the bottom line? First, the bad news. Rocío

Molina, one of the most original and gifted dancers of recent years,

has fallen into militant anti-stereotypism. Her style has become

watered-down and mainstream contemporary, her flashes of genius

are too brief and too few and she’s lost the sense of humor

and intelligent irony that allowed her, at the tender age of 20,

to wink lovingly and freshly at dance from times past – oldies

but goodies, convincingly reworked – can there be anything

more admirable and difficult? Rocío Molina has the creativity,

preparation and genius of Israel Galván, and that’s

quite a mouthful. Now all she needs is his bravery and decision

because in her hands, feet and body is the capacity to open new

paths in women’s flamenco dance. That was the good news.

More information:

'Málaga en Flamenco'

Special. All the information.