|

FESTIVAL DE FLAMENCO DE NIMES

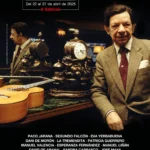

Juan José Amador, Fernando Terremoto, Chiquetete

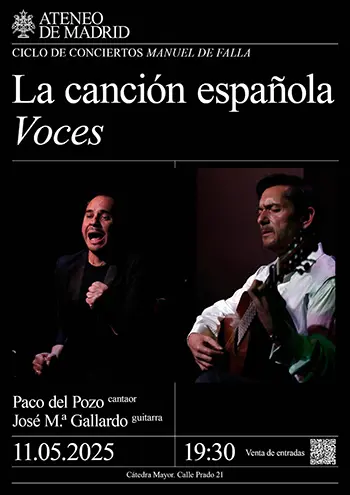

Thursday, January 22nd, 2009. 8:00pm. Teatro de Nimes (France) Festival de Nimes 2009 – All reviews

|

|

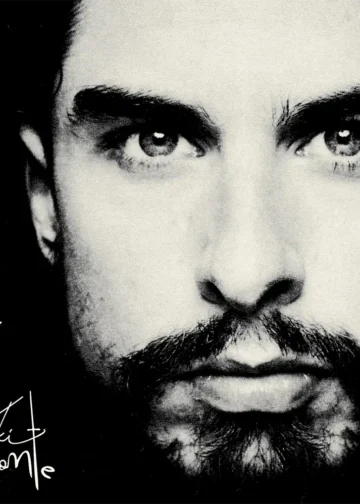

Part one. Juan José Amador, cante. Eugenio Iglesias, guitar. Text: Estela Zatania It was announced somewhat hyperbolically on the program as “Three Voices for History”. A humbler, more apt title would have been “Three Unmistakable Voices”. Because if anything is remarkable about the three singers in this shared recital, and if anything is lacking in the current panorama of flamenco singing, it’s personality. That certain something that lets you identify the interpreter from the very first “ayy”, beyond all possibility of error. There have always been “isms” in flamenco singing. Mairenism and Caracolism that turned Antonio Mairena and Manolo Caracol into cult figures, were abruptly displaced by Camaronism, the overwhelming movement that revolutionized, not only flamenco singing, but the concept of the flamenco genre. Juan José Amador, Fernando Terremoto and Chiquetete, because of the era in which they came of age, were touched, each one in his own way, by Camaronism, but the classic cante of old maestros also resides within each one of them. Juan José Amador, of the numerous Amador family that includes innovators such as La Susi and Raimundo Amador, made a recording in the early seventies, like so many other young people, riding on the coattails of Camarón. It was more experimental than traditional, and passed without making a ripple to be lost in the great sea of pseudo-flamenco music of the era. But Juan José was able to reinvent himself. Thanks to his knowledge of cante, his command of compás and a lovely deep voice with dense flamenco overtones, he became one of the most sought-after singers for dance, and several unforgettable works, most notably “La Mujer y el Pelele” of Isabel Bayón and “Cuando uno Quiere y el Otro no” of Marco Vargas and Chloé Brule, would be unthinkable without his multitalented participation as actor and guitarist, in addition to cantaor. It’s not common to see him singing alone, without dancers, but his performance in Nimes was disappointing. He sang mining cante with abandolao, soleá, fandangos, cantiñas, bulerías and martinete in a rushed and inconsequential manner, without adequate endings. It’s not that singing for dance spoils the singer as some people say, but rather that Juan José Amador has never cultivated a solo career, and he was little prepared for this challenge. Nevertheless, he received, along with the interesting guitarist Eugenio Iglesias who played for him, the heartfelt applause of audience and peers whose admiration he has enjoyed for three decades. Fernando Terremoto is the youngest of the trio of singers, but the one most deeply rooted in tradition, mostly due to the mega personality of his father, Terremoto de Jerez, one of the most revered flamenco singers of all time. With his astonishingly resonant voice, and without deviating from the most rigorously traditional line except for the discreet percussion of José Carrasco, he managed some brilliant moments despite constant problems with the sound. His malagueñas now have the subtlety that used to be missing, his siguiriyas and bulería por soleá recall his illustrious father and hometown, and to wind up, bulerías with “mare Manuela” and delightful dancing. A mish-mosh of tones when Fernando sang at the front edge of the stage without amplification, was quickly sorted out by the admirable Alfredo Lagos; two great professionals who provided the best performance of the evening. Chiquetete’s professional background is anything but conventional. Like Juan José Amador, he belongs to that generation that rushed through the door opened by Camarón. Not content to innovate from within flamenco, he was practically the first traditional singer to jump the fence to the “other side”, using his velvety voice for a vast repertoire of flamenco-tinged pop songs, to become an international star. Now, possibly because of his age, Chiquetete is struggling to regain his place within the world of flamenco. With his elegant appearance and impeccably sculpted white hair, he began promisingly with tonás, and the communicative power and intense delivery were right in place. In soleá de Triana, one of his great specialties, with the flavor that only comes with first-hand knowledge, and the moderation of maturity, he was still convincing. It was when he went into a lighter repertoire, tientos tangos, that there was no energy, his voice barely sounded and only brief flashes reminded us of who this man used to be. Fandangos which ended with Huelva had some high points, and alegrías de Cádiz and de Pinini also had some flavorful moments. But in general, it was an exercise in nostalgia, and a failed attempt to return to the past.

|