|

Agujetas en Rota |

|

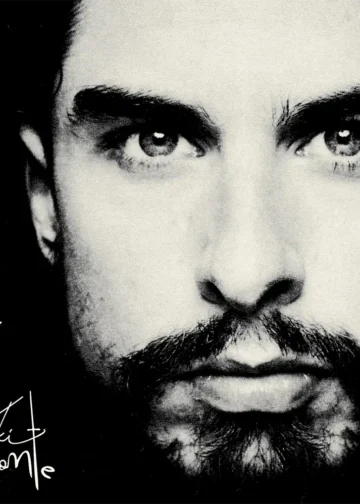

Texto: Estela Zatania Cante: Agujetas de Jerez, Diego Agujetas, Gitano de Bronce. Guitar: Antonio Soto. Dance: Kanako. THE LAST FLAMENCO SINGER A sleepy fishing-village on the Costa de la Luz that became a haven for tourists. A theater that was half-empty despite the very reasonable entrance fee. No programs, and apparently no media presence. It was one of the most relevant and extraordinary flamenco events of the year.

Manuel de los Santos Pastor, “Agujetas”, used to like to say there were only two flamenco singers: himself and Chocolate. When the latter passed away a couple of years ago, that short list was irrevocably reduced by half, and we’re left with the old lion. Obviously there are other singers, but Agujetas isn’t completely off the mark: with his faculties, characteristics and family background, his capacity to invoke the elusive “duende” and deliver the “black sounds”, it wouldn’t be impossible to name others, but certainly very difficult.

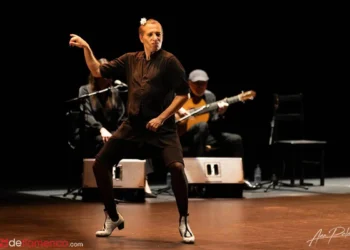

The curtain opens and Diego Agujetas, Manuel’s brother appears, arms waving overhead like a victorious soccer player. Málaga guitarist Antonio Soto, who will remain on stage for the nearly two and a half hours without intermission the recital lasts, sits alongside. The formula followed by Diego, and by the other members of the family, is soleá, siguiriya and fandango. For those who complain it’s always the same old limited repertoire, take note: in those three forms alone is a universe of styles, and the cante connoisseur enjoys each one as if it were the first time. Repeating styles, mixing odds and ends of different geographical origin, unidentifiable fragments and completely original touches, even repeating some verses, every second is full of surprises. This is when you realize how little importance styles and verses have compared to what the singer contributes, which is ninety-nine percent, the color of each individual personality. Diego’s way of singing is unmistakably of the family, but with a painful delicacy Manuel lacks and which is reminiscent of the father. There are shouts of “Diegoooo!”. Fandangos valientes, malagueña del Mellizo to vary the menu, but differently from how we’re accustomed to hearing it, and to end, a brief tale of Moorish battles set to a romance por soleá. Diego Agujetas (photo: Paco Sánchez) “Gitanillo de Bronce”, Miguel Pastor de los Santos, cousin of Manuel and Diego, picks up the gauntlet. Dressed and coiffed like a true dandy, his extravagant appearance seems destined to distract attention from any possible deficiency in the singing, but the man shows what he is capable of, wrestling with diminished faculties, calculating just right and offering the only bulerías of the evening with verses that recall Tío Chalao and the Plazuela, with the occasional wink for el Chozas. And all the while, Antonio Soto, like the old masters, from the days when the cante ran the show, not the guitar, doesn’t take his eyes off the singer for one moment. He deserves kudos for managing to accompany these anarchic voices thanks to his knowledge and good taste.

The stage is empty for a few minutes awaiting the arrival of the patriarch. When finally he appears there is a warm ovation, and Agujeta is visibly grateful, in fact, he appears to be in high spirits and has come to deliver the goods. He starts out with soleá, and instinctively you want to place the styles, but it’s a grand potpourri, done with good sense and style, cante in its most natural state. Rather than repeating existing forms, Manuel finds his own, taking inspiration from cante handed down in his family. As is his custom, he employs short bursts of cante, two or three styles and that’s it, then he gets into soleá again, and again closes out… It’s a structure that doesn’t quite work in recordings, but in live performance makes perfect sense, because he’s not looking for applause, but rather something more important and elusive. In siguiriyas he gets that nasal aching sound, without resorting to the dramatic closing styles used by others, ending with a simple gesture of the hand. He sings his fandangos, inspired but disorganized, five lines, maybe four, Soto is sweating bullets, taking on everything Agujetas comes up with, and the singer is wearing a mischievous smile, pleased with himself and with the audience’s effusive reaction. He shares his “gazpacho” with Soto, there is laughter, applause, the theater becomes an old-style Andalusian tavern. Agujeta asks the audience what they want to hear: “cantiñas!” shouts one. “Carapiera!”…”tientos!”…”martinete!” “Okay, okay” roars the lion, “bulería pa’ escuchar”, and Soto puts the capo on 7 in E position…this is Manuel Agujetas’ party and we’re his guests. Next, “I’m going to do something very old that my father used to sing”, and it turns out to be some old-sounding tonás, with a peculiar, acrid sound.

His son Antonio comes on to mercilessly shred our souls to the compás of siguiriys. Kanako, Agujetas’ wife, dances bulería por soleá and a dance of footwork combinations with a cane and no music. The patriarch soldiers on with soleá, fandangos, malagueña; Chacón would be amazed at what Manuel does with his creation. And when the clock says it’s past eleven-thirty, everything comes to an end with another siguiriya and the audience’s standing ovation.

|

Without passing through any intellectual process, rejecting all superficiality

Without passing through any intellectual process, rejecting all superficiality