XVI Festival de Jerez 2012 XVI Festival de Jerez 2012

muDANZAs BOLERAs 1812-2012

|

|

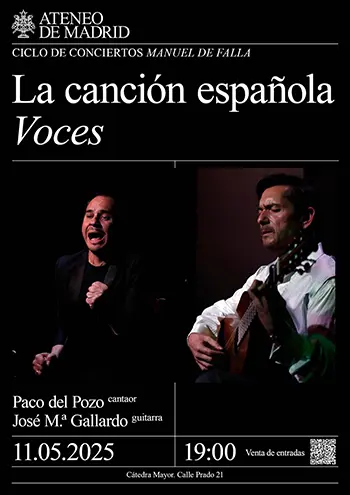

Text: Estela Zatania FROM BULERÍAS TO BOLEROS PEDRO EL GRANAÍNO Last year the work “Homenaje a los Grandes” of dancer Farruca, featured singer Pedro el Granaíno. On that occasion this artist, one of the regular singers of the Farruco family, surprised a lot of people, and I wrote that “he not only masterfully evoked Caracol […] but recreated the work of other historic maestros of cante, and gave substance to a large part of the show with the toasted honey of his Camarón delivery”. This man was a real discovery, and that triumph led to his presence this year in the program of acoustic cante at the Palacio Villavicencio. With the excellent guitar of Juan Requena, the singer began with granaínas were wrapped up with jabera, and never has an abandolao cante had such a flamenco impact. In a soft-spoken manner, and a little nervous, Pedro declared that this evening he was fulfilling the dream of a life-time giving a recital at the Festival de Jerez. A bit more relaxed now, he sang soleá to the compás of bulería por soleá, with the slow tango “Mentira es…” skilfully inserted, confirming the flexible nature of this rhythm and the singer’s strong Camarón identity. Malagueña was ended with the Frasquito Yerbabuena style, and for siguiriyas he sang no fewer than five verses including Torre, Lacherna…the man knows his flamenco and has a sincere intense delivery. Bulerías with lots of substance were dedicated to “José” (Camarón) as this year it’s been two decades since his premature death. Two encores, fandangos and bulerías, were necessary to calm the excitement of a very appreciative audience.

muDANZAs BOLERAs 1812-2012 – Video Cast – The Romancero and choreographer: Francisco Velasco (guest artist). Dance teacher: “La Campanera” (guest artist). The Maja: Elena Miño. The Bullfighter: Daniel Morillo. The French Lady: Myriam Manso. The Majo: Sergio Bernal. The Festival de Jerez is an event that welcomes the diversity of Spanish, folkloric, semi-classical and flamenco dance. On Monday night, the work “muDANZAs BOLERAs” was presented with the ambitious intent of being “a journey through time […] in which we will discover the essence of the Escuela Bolera” as it says in the program. From the time you start delving into flamenco’s past, you see old engravings, prints and drawings with intriguing titles like “Dance of the Gypsy”, “Danse Gitane” and such that stimulate your curiosity and feed certain romantic ideas we all have. Inevitably, the images turn out to be of a sweet young lady in ballet slippers pointing her toe out in a dainty pose. So much for romantic preconceptions. The fact is, the fascination with Spanish culture that caught Europe’s collective imagination two centures ago, was based in large part on the immense bolero school of dance which today has its most popular expression in the sevillanas that are sung and danced all over Spain. The audience for this show was notably and demographically different from what we’ve been seeing at the Villamarta other nights: middle-aged people or older, with a majority of women. The work began with smoke. Lots of smoke that reached to row 16 where I was seated. It’s a dramatic effect that sets the scene for 1812 in times of war. From that moment on there is a series of dances, nearly all in couples or groups (usually the dead giveaway that separates this branch of Spanish dance from flamenco), and all instrumental but for a brief abandolao fandango. The sweet music and gentle movements of the dancers seem to belie the historic moment, but it’s clear the investigation, documentation and choreography carried out by Juan Vergillos, Rocío Coral and guest artist Francisco Velasco are absolutely reliable. The beautiful wardrobe and carefully designed hairdos evoke the era with clarity and reflect the careful preparation that went into this show, while bringing to mind those old engravings of Fanny Elssler and others who caused such a stir with their “gypsy” dances that don’t seem so gypsy to us in retrospect. We see the importance of soft slippers, but heeled shoes are also used. You realize the exclusivity of musical measures of three as opposed to today’s popular music, nearly always “binary” – in lay terms, think of the difference between a waltz and a rumba. The flamenco follower is able to recognize the occasional fandango, the pre-sevillanas which is seguidillas and melodic threads that suggest the Boda de Luis Alonso and El Vito. The rest is quite homogenous with the exception of a brilliant interpretation by Velasco when he portrays a drunk dancer. Upon reading the program we discover all the music was “inspired in melodies of the 18th century”. The historic and educational intent doesn’t really come through, and I would have like more detailed information in this respect. |