An essay by Brook Zern

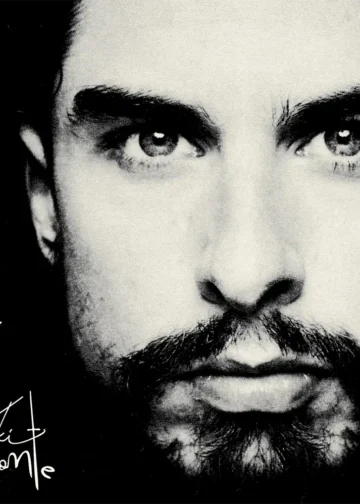

Photo by Luis Castilla/La Bienal

Spain's greatest master of flamenco's deepest and darkest song styles died today, Christmas day, in Jerez de la Frontera, the last bastion of the traditional art.

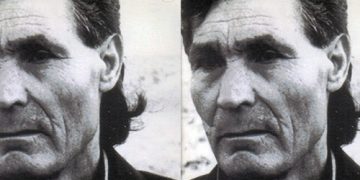

Manuel Agujetas, born Manuel de los Santos Pastor in 1939, was a blacksmith from one of the most important Gypsy families of southwestern Andalusia, the birthplace of flamenco. As a man, he was often difficult and sometimes impossible, and he left a trail of damage and detractors in his wake. As an artist, he graced the world with a kind of flamenco singing that will always be treasured by the relatively few aficionados who revere this lacerating, even terrifying art.

When he emerged as an artist around 1970, his approach fit the reigning aesthetic – the best and purest flamenco was the most gripping and profound. The key measure was command of the so-called cante jondo, or deep song – the martinetes, the siguiriyas and the soleares. Agujetas transmitted their mysterious power like no one else. He sounded ancient

But change was in the wind. The immortal guitarist Paco de Lucía had just teamed up with the young Camarón de la Isla, a Gypsy who sang many styles but specialized in two lighter forms, the bulerias and the flamenco tangos. Their art revolutionized flamenco, giving it a contemporary feel that captivated a new generation.

Around 1990, another aesthetic started to regain importance in the world of flamenco song. It was pleasing, appealing, often beautiful. Hard-core purists dismissed it as an echo of the “cante bonito” or pretty song that had dominated the art from the 1930’s to the early 1960’s. But after decades in the shade, it was back in fashion. The rough and cutting voice, often linked to Gypsy artists, was out. Flamenco song was once again easy to listen to.

In Jerez, they still aren’t buying into the nice noise. For years, the most respected elders have been insisting that when Agujetas dies, it’s all over. Not literally, of course – there are dozens of remarkable singers who manage to evoke the eerie power of deep song. But Manuel Agujetas, like him or hate him, has been the incarnation of the one quality that sets flamenco apart from other arts: the duende.

During the past half-century I’ve spent decades in southern Spain. I usually say I’ve been searching for good flamenco, and I’ve seen endless hours of that. But I’m actually trying to find the duende, and that is rare indeed. During the few dozen instances when it materialized, nearly half were in the company of Manuel Agujetas.

He is gone now, but you can see what the fuss was about by simply going to YouTube and entering his name. If you enter the additional word “rito”, you’ll see him in a 1972 docunentary film series “Rito y Geografúa del Cante Flamenco”.

(I tried to buy a copy of that entire great 100-film series from Spanish National Television that same year, but it would take fifteen years of begging before I was allowed to pay a whole lot for the first copy.) Among the many great artists shown, I especially wanted the episode on Agujetas because I knew he lived dangerously, and was afraid he wouldn’t be around very long. Yesterday, Agujetas was one of the few featured artists who was still alive. He was amazing. We will not see his like again.