Brook Zern

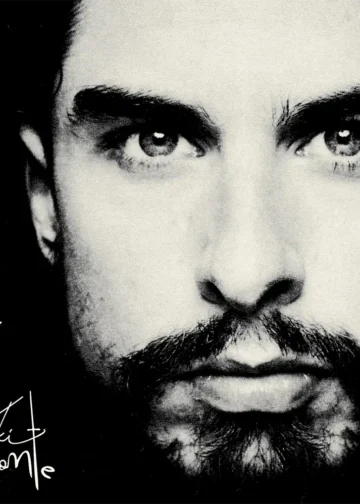

Diego An essay by Brook Zern on guitarist Diego del Gastor on the fortieth anniversary of the latter?s passing.

Ten years ago I wrote this essay on guitarist Diego del Gastor who passed away in 1973. I was one of the dozens of foreigners, mostly Americans, who had studied with him in the final decade of his life. I wanted to explain and justify the admiration and even the love we felt for the man and his art – a very high opinion that was not shared by most flamenco performers, authorities and Spanish experts who knew much more than we did.

Today, the situation has changed somewhat. In 2008, the centennial of Diego was marked by many special events, articles and institutional honors, in addition to the first commercially produced recordings that documented a small part of his art, and his long professional career. Also, the tremendous unexpected success of the instrumental group Son de la Frontera, and its successor SonAires de la Frontera, was mostly due to Diego’s catchy music of personal creation that his followers had treasured throughout the years, without imagining just how popular he would become among a future generation born after his death.

Nevertheless, the figure of Diego and the value of his art are controversial topics. The magnificent artist and supreme star Paco de Lucía has, for all practical purposes, obliterated the flamenco that used to be, submerging the guitar in jazz combos and a kind of music inspired above all in harmony – something Paco considered the crucial element that was lacking in flamenco before the revolution he himself triggered.

For me and for many other non-Spaniards coming from a Western culture in which musical harmony is supreme, the glory of the flamenco tradition was precisely its lack of harmony – in other words, the focus on the monodic melody that gives flamenco its exotic Eastern sound, so unique and so evocative of the mystery of legendary Spain.

Diego del Gastor, the Gypsy flamenco guitarist of Morón de la Frontera, died thirty years ago on July 7th, 1973. Even before his death, there was serious controversy about his stature as an artist. It has intensified in recent years. The debate is inextricably linked to the fact that many non-Spaniards thought very highly of the man and his playing, and his reputation became greater outside of Spain than within it.

The question of Diego del Gastor’s stature as a guitarist must be viewed through a very specific filter.

Of course, there are other cases in which a flamenco guitarist’s story is linked to non-Spaniards. Carlos Montoya left Spain for New York as a young man, and his idiosyncratic but crowd-pleasing music found a huge audience in the U.S. and abroad at a time when a solo concert career was simply not an option in Spain.

The young Sabicas also came to the new world and settled in New York, where his magnificent virtuoso playing commanded far larger and more appreciative audiences than Spain could have offered. Another fine virtuoso, Mario Escudero, also found success by leaving Spain for New York. Juan Serrano came to the new world as the protégé of the popular folksinger Theodore Bikel, and managed to carve out a career. And the flamboyant French Gypsy guitarist Manitas de Plata was widely, if incorrectly, hailed in America as a brilliant flamenco player and technical wizard, enjoying huge financial and popular success.

His reputation outside Spain acquired such a powerful mystique that some Americans and other non-Spaniards journeyed to Morón to seek him out

But the case of Diego del Gastor was quite different. He was not flamboyant, not a virtuoso, and had no intention of becoming a concert soloist, or even famous. He made his living as an accompanist, working with singers who happened to come to Morón or joining them in nearby towns.

Nonetheless, his reputation outside of Spain acquired such a powerful mystique that some Americans and other non-Spaniards journeyed to Morón de la Frontera to seek him out.

In large measure, though not completely, this was due to the writing of Don Pohren, an outstanding flamencologist whose first book, The Art of Flamenco, was published in 1962. At a time when there was very little reliable information on the topic, Pohren offered perceptive insight and deeply-researched analysis. He also spoke very highly of this virtually unknown player who had an almost magical ability to transmit the vast emotional range of flamenco – its grief and pain, its joy and affirmation – though the guitar.

Even before Pohren’s book was widely known, I and some other American aficionados had learned of Diego del Gastor’s playing from two young U.S. players, Chris Carnes and David Serva, who had studied seriously with him. Soon, more non-Spaniards joined those who were already living in Morón.

A few years later, Pohren bought the Finca Espartero, a sort of hacienda just outside of the town, and opened it to paying guests as new way to experience serious flamenco. Soon a steady stream of visitors was coming from around the world to hear flamenco in Morón, including the playing of Diego del Gastor.

It was assumed that one was hugely privileged to have found this place, and this man, and this magical music.

The tendency among these non-Spaniards was to take the general claim of Diego’s great artistry at face value. It was assumed that one was hugely privileged to have found this place, and this man, and this magical music. And that someday, this would be the stuff of legend, and there would be universal confirmation of the importance of this special moment in the story of flamenco.

However, great love stories are rarely as simple as that. A few complications are always in order. For one thing, Diego del Gastor had never faced one acid test that guitarists normally had to pass in order to attain full recognition from the flamenco world at large. He had never devoted his life to going where the major professional action was. In his youth, he hadn’t joined the traveling shows that brought flamenco to stages and even bullrings around Spain (well, he had, briefly, accompanying the very important singer Manuel Vallejo, but he had not liked the restrictions on his playing, and he soon left).

Later, he did not work at the tablaos or flamenco nightclubs that supported so many professionals. And he never hooked up with one singer to do a circuit of performances that could guarantee a steady income.

In fact, he chose to stay home. Not literally, of course – flamenco guitar was always his profession, and he sometimes went into Seville or to various smaller nearby towns to accompany singers. Still, many flamenco artists never saw him at work, and had no way to appraise his playing except by hearsay.

When offered a rare chance to make a serious recording for a prestigious Spanish label, he decided against it.

In other ways, too, he refused to do what was expected. He didn’t wait in for hours in dingy promoters’ offices, hoping for work, as so many giants of flamenco have done. He didn’t pay obeisance to other artists who might help to guarantee his reputation. He refused to accompany singers when he didn’t like their art – including Antonio Mairena, widely regarded as the greatest singer of his era. And when offered a rare chance to make a serious recording for a prestigious Spanish label, he decided against it. In short, he did only what he wanted to do, and he willingly paid the price by living in near-poverty for much of his life. Diego del Gastor simply wanted to make a living by accompanying great singers. In this, he succeeded.

Today we are left with an interesting, perhaps surprising question: Was he any good?

He frequently accompanied Manolito de la Maria, the supreme maestro of the great form of soleares called the soleá de Alcalá. He frequently accompanied Juan Talega, who was the living embodiment of the deepest Gypsy forms of siguiriyas and soleáres, as well as the profound unaccompanied martinetes. He frequently accompanied La Fernanda de Utrera, Spain’s greatest living cantaora of the last half-century, and the quintessence of the great soleá de la Sarneta. He frequently accompanied his brother-in-law Joselero de Morón, a noted interpreter of soleáres, tangos and bulerías.

He frequently accompanied Fernandillo de Morón, a remarkable interpreter of festive Bulerías. He sometimes accompanied el Perrate de Utrera, a master of serious song, and La Perrata de Utrera, a repository of serious flamenco and great Bulerías, and Juan El Lebrijano, one of a handful of superb Gypsy singers of a wide range of flamenco, and Anzonini, a master of dance and song. He also accompanied dozens, perhaps hundreds of other singers over the years, including Spain’s greatest living singer, El Chocolate. And yet today, we are left with an interesting, perhaps surprising question: Was he any good? Even before the death of Diego del Gastor, and certainly since, there has been a reaction – even a backlash – against the assumption that he has a valid claim to greatness.

In 1965, I asked the guitarist Pepe Martinez, famed both as a concert artist and as an accompanist, about Diego. “Some primitive who lives in the mountains”, was the reply. It was dismissive, but understandable. After all, Pepe Martinez was a direct disciple of Ramón Montoya, the Gypsy virtuoso from Madrid who virtually founded the flamenco guitar as an instrument in its own right, and was revered both as an accompanist and as pioneering occasional soloist.

Enormously compelling for some, but apparently off-base or misguided to others

The aesthetic of Ramón’s great artistry lay in his search for sweetness, for a kind of beauty that a classical musician would readily grasp. He was at his greatest exploring the lyrical sweep of the gorgeous tarantas, the captivating liquid trickle of the granadinas, the tonal majesty of his great instrumental rondeña – all of which are played in a free rhythm, rather than in the strict metrical form called compás that defines most flamenco forms. And this same quest for a refined beauty and elegance also permeated Ramón’s great work in flamenco’s more grave and cutting rhythmic forms, like the soleá and sigiuiriya. In addition, Ramón Montoya’s domination of the guitar depended on a wide variety of techniques, many borrowed from classical guitar. Notably, he made full use of the lovely tremolo as well as the flowing arpeggio techniques for the right hand.

And, like a classical musician, he made full use of the entire fingerboard, to extract a relatively full melodic range from the instrument. While his music was beautiful at its best, it was sometimes merely pretty – not necessarily a virtue for those flamenco styles derive their power from a raw, almost primitive earthiness.

Diego del Gastor took a very different approach. Influenced by a countervailing style fostered by the Jerez guitarist Javier Molina, and also influenced by an earlier Morón guitarist named Pepe Naranjo, he sought a different sound, direct and enormously compelling for some, but apparently off-base or misguided to others. Technically, although Diego ultimately learned some classical guitar and sometimes employed its techniques, his finest playing emphasized the older-sounding, and seemingly simpler thumb runs in the bass strings. This, along with strong picado or rapidly plucked runs and his strong rendition of the characteristic flamenco “roll” or rasgueado strum for chords, formed the backbone of his art.

And, interestingly, Diego chose not to play most of the flamenco repertoire at all. In fact, he devoted his entire artist life to just three of flamenco’s more than fifty forms. He worked at his siguiriyas, his soleares and his bulerías. For each, he developed an immediately recognizable – and infuriatingly hard to replicate – sound and underlying rhythmic pulse within the inviolable compás. This is what is generally treasured in flamenco circles as the “sello propio” – the player’s own unmistakable stamp.

Diego concentrated his full power on the three forms he truly loved.

As a professional, of course, he had to accompany virtually everything at one time or another. And he spent some time on other forms, inventing some remarkable music for the alegrías, tangos, tarantas and granadinas. But he controlled his own creative life to an astonishing degree, and he gravitated to artists who shared his view about the supremacy of these forms. He concentrated his full power on the three forms he truly loved. And so the question of Diego del Gastor’s stature as a guitarist must be viewed through a very specific filter. He didn’t seek prove himself, he didn’t use the full melodic or harmonic range of the instrument, he didn’t emphasize some important techniques, he wasn’t a concert virtuoso, and he didn’t want to play most of the repertoire.

It would seem that there is not much left. But something indeed is left: the challenge of doing justice to flamenco’s most demanding styles by playing exactly the right notes and chords in exactly the right way. Did Diego del Gastor do that? I happen to think he did. But as a born outsider, I always find it difficult to trust my own judgment about flamenco artists.

Still, for whatever it’s worth, I think that Diego del Gastor’s soleá is the best I’ve ever heard. After 40 years, I still love to try and play it – in addition to the great soleares of Nino Ricardo and Melchor de Marchena. And I think that Diego del Gastor’s siguiriyas is almost as good as Melchor’s, and even better than Ricardo’s and Paco de Lucía’s and Perico del Lunar’s. And I think that Diego del Gastor’s bulerías are utterly unique, and probably even incomparable — although I also love those of Sabicas and Morao and Paco Cepero and Paco de Lucía, among many others.

Guitar for guitar’s sake has never been highly valued in Spain

Of course, these observations are largely guitar-centered. And even if they were correct, they would not really answer the question at hand. In fact, guitar for guitar’s sake has never been highly valued in Spain. It’s all very nice if a guitarist can play engaging material in a convincing way, but in flamenco circles a player’s reputation really rests on his ability to properly accompany serious singers. I found it unnerving to learn that a number of knowledgeable artists felt that Diego was not a good accompanist.

The general tenor of this criticism relates to something that was evident enough. The perfect accompanist, according to many aficionados and artists, should be all but invisible. He is there only to support the singer, and that means never calling attention to himself. He should only play his falsetas or melodic riffs when it’s clear that the singer is resting, gathering his resources for the next verse. He should never do anything that might be interpreted as intruding on the concentration of the singer.

The falsetas should always be brief, illuminating the performance without commanding serious attention or distracting the audience or the singer. Well, I heard Diego accompany a lot of singers.

And the only time he fully fit this traditional mold was when the singer was inexperienced or untalented. When the singer was a full-fledged master, as was usually the case, Diego del Gastor could be assertive in an unusual way. Here he felt free to violate the general rule; he clearly believed that by giving his all, he could induce a great singer to reach deeper within himself or herself. It was always clear that there were two exceptional artists at work, not just one. There was a dialogue, an interchange, a series of challenges and conflicts and glorious resolutions.

Two artists at the peak of their form, bound in a powerful symbiotic lock.

To see Diego del Gastor accompany Fernanda de Utrera all night long – hours and hours spent almost entirely within just one form, the soleá, and during which Diego kept returning to just a few of his hundreds of falsetas – was to witness two artists at the peak of their form, bound in a powerful symbiotic lock that drove both peak expression. The same phenomenon was in play when I saw Diego accompany Juan Talega; but the feel was different, because Talega was quite old and Diego didn’t ever push hard. Instead, he established a conversational link with Talega. He was never self-effacing, as a younger player should have been; but he was never overpowering, and he managed to draw out the best of Talegas’s remaining strengths.

With Joselero, Diego displayed yet another approach. These two men were dear friends, contemporaries and brothers-in-law, and here the equation was singular. Joselero was highly respected but was hardly a candidate for immortality, and he knew that in Diego, he had more than met his match. Here Diego would often take center stage, knowing that this particular singer was delighted to work in the presence of this astounding guitarist. The result was unorthodox, but again, it consistently drew the best from this particular situation.

Certainly there are some flamenco artists who had serious reservations about Diego del Gastor.

Certainly there are some flamenco artists who had serious reservations about Diego del Gastor. At times, this fact has been extended into an assertion that the negative view is essentially unanimous. I tend to discount this, not only because I find unanimity to be quite rare among flamenco artists, but also because I have heard Juan Talega and Manolito de Maria and Juan el Lebrijano and Ansonini speak highly of Diego del Gastor’s artistry as an accompanist.

I have also heard Fernanda de Utrera speak very highly of Diego as a person, a guitarist and an accompanist. I believe there may have been some ambivalence on this last appraisal at certain times in Fernanda’s life, in part because she sometimes seemed to feel that the countless hours she had spent singing in situations like those with Diego ultimately cost her her voice; (you can hear that fabulous flamenco voice beginning to give out at the last moments of her performance in Saura’s film “Flamenco”).

I believe that Fernanda’s sister Bernarda harbors some negative feelings about Diego, which is regrettable. But for me, the essence of the relationship between Fernanda and Diego could be seen best in their eyes when they worked together – the adoration seemed palpable – and also in a muttered comment she made while he played: “Ni Beethoven, ni sus muertos”, an untranslatable appraisal that sort of says “You can take that Beethoven guy and his whole family…”

I was also interested to hear from one respected American player that Camarón was apparently fascinated by a recording he heard of Diego, and spoke highly of it. And I was delighted to see that El Chocolate, in his reminiscences about his 70 years as a great flamenco singer, singled out a night he spent with Diego del Gastor and Nino Ricardo – also a documented admirer of Diego’s art – as one of the highlights of his life.

Speaking of guitarists, I’d add that Sabicas was always very interested in the playing of Diego del Gastor, and seemed to enjoy it immensely. On many occasions in New York, he and his brother would hand me a guitar and ask me to play it. While I never came close to doing it justice, they evidently made due allowances and were always fascinated by the way it worked. I even believe the story that Sabicas once approached Diego about doing a recording together, although I can’t imagine what the result would have been considering the disparate nature of their styles. However, it is the opinion of Paco de Lucia that may have the greatest influence on the evaluation of Diego del Gastor in the future.

And Paco, who has already secured his place in history as the greatest guitarist flamenco has ever seen, does not seem very impressed by Diego del Gastor. In an appraisal contributed to a recent book on flamenco guitar in Morón, he said in essence that while the man had a notable way of playing uncomplicated material in a moving way, he considered the whole Diego phenomenon vastly overblown. He made it clear that he thought it was a combination of marketing hype by Don Pohren and the hippy era of the ‘60s that somehow combined to make a mountain out of a molehill.

However, it is the opinion of Paco de Lucia that may have the greatest influence on the evaluation of Diego del Gastor

There are many ways to look at this view, which is hardly unique to Paco de Lucia. First, it seems to fundamentally mistrust foreigners, assuming that what we like isn’t necessarily very good. (In fact, I can understand this — I myself tend to be suspicious of any traditional musician who is appreciated more by outsiders than by insiders.) Also, I suspect that Paco may have resented hearing many Americans enthusiastically tell him about Diego, all tacitly assuming that they had recognized a great artist who had been grossly neglected and underappreciated by Spain’s flamenco community. Finally, assuming that Paco has heard at least some of the recordings where Diego is playing at or near his best, I suspect that Paco just doesn’t relate to this particular kind of retro-sounding flamenco guitar. Diego’s style would seem to represent everything that Paco’s particular genius has all but eradicated – a narrow pallet of chords and narrow melodic range, a reliance on straight-ahead rhythm instead of complex counter-time, an avoidance of outside influences from other musical genres.

It’s unjust to dismiss Diego del Gastor as the product of moonstruck or drug-addled hippy trend-seekers.

Regardless of the specifics, I think it’s unjust to dismiss Diego del Gastor as the product of moonstruck or drug-addled hippy trend-seekers. (For whatever it’s worth, I was cold sober throughout the years I spent in Morón and vicinity, even during the year or two when a few actual hippies blew in and out of town and hung around a while before getting bored. I think Paco denigrates the man and his memory by appraising Diego entirely in the context of one particular moment in his lifetime, and by the fact that he attracted the attention of some foreigners.)

There is a further implication that Diego was really nothing special, and that many towns throughout Andalusia had artists of similar aptitude who just didn’t happen to fall into the spotlight. (I wish it were so. I spent many months in many towns, looking for such extraordinary guitarists. I even found a few very interesting players in the process. But none of them were remotely in the league of Diego del Gastor, with his seemingly inexhaustible wealth of music and depth of expression.)

A final observation about Paco de Lucia’s appraisal: It seems that he does not voice the allegedly common complain that Diego is too assertive in his accompaniment. This is hardly surprising, since the other guitarist who was a palpable presence in his most notable accompaniment was Paco de Lucia himself – not with older singers, but with his contemporary genius, Camarón. Here Paco’s role was so intensively notable – even intrusive, in a positive sense of the word – that he was listed on album covers not as guitarist or accompanist, but as “special collaborator”. Precisely.

Paco and Camarón collaborated to make their crucial statement about the future of flamenco. Their mutual contributions as virtual equals defined the resulting art. They drove one another to astonishing heights. Clearly, the flamenco world would have lost something marvelous if Paco de Lucia had settled for meeting the traditional demand – that he be an all-but-invisible accompanist of Camarón’s singing, never shining and never playing any of his brilliant extended falsetas that were theoretically too long for proper accompaniment.

Happily, Paco knew better. He knew when to break the rules. And he was certainly good enough to justify such a radical step. Well, I believe that Diego del Gastor did essentially the same thing when he worked with great singers, years before Paco de Lucia. The context was different, of course – there was no intention to create a revolution, but simply to attain maximum effect and artistry; but the result strikes me as equally impressive. There are extensive live recordings of Diego at his best, both accompanying excellent singers and playing solos.

Virtually all, however, are private recordings that for one reason or another have never been properly published. I’m convinced that someday, they will see the light of day, and it will be possible for the world to make a definitive judgment of the man’s music. Until then, we’ll have to settle for the few random recordings that have been issued, and also the films of Diego accompanying La Fernanda and La Bernarda de Utrera, Perrate and Joselero as well as playing some solos – but only occasionally displaying his real powers – that were issued as part of the “Rito y Geografía del Flamenco” series, and partially reprised in “Rito y Geografía de la Guitarra”.

Some artists who have grave reservations about Diego, have no such qualms about Paco del Gastor

Another way to obtain a taste of Diego’s style is to listen to his nephews, though none sound just like him. Paco del Gastor in particular has earned a considerable reputation in Spain, and his powerful guitar shows one aspect of Diego’s style; in fact, some artists who have grave reservations about Diego have no such qualms about Paco. Other aspects of Diego’s art are evident in the playing of nephews Juan del Gastor and Diego de Morón, as well as Agustin Rios (who lives in California).

David Serva’s remarkable music has evolved considerably since he was simply Diego’s outstanding foreign disciple, but it also reveals much of the essence of the original inspiration. Several other foreigners have managed to capture his elusive style, notably including Steve Kahn and Ian Banks in New York.

There are even some young Spanish guitarists who play some of Diego del Gastor’s music, often to excellent effect. True, there may not be very many – but considering the upheaval in guitar that has followed the de Lucia revolution (which Paco himself sometimes refers to as a “virus”), essentially eradicating the memory of so many outstanding players of the past, it seems that Diego’s singular art has fared relatively well.

His life was a lesson in generosity of spirit.

As for me, I’ve never really wavered in my original conviction that Diego del Gastor was a truly great and rare artist. He was also, in my eyes, a great person. To me, his life was a lesson in generosity of spirit, in retaining enormous dignity in the face of enormous difficulty, in achieving personal independence at huge cost, and in gladly sharing all the wealth of deep humanity, creativity and glorious artistry for which he paid so dearly. I believe that the artistry of Diego del Gastor, neglected as it was when he lived and questioned as it has been after his death, will ultimately be recognized as enriching the world of flamenco, and the far broader world of music. In the meantime, there’s one thing I know for sure: It has enormously enriched my life.

Brook Zern in 1968