Estela Zatania

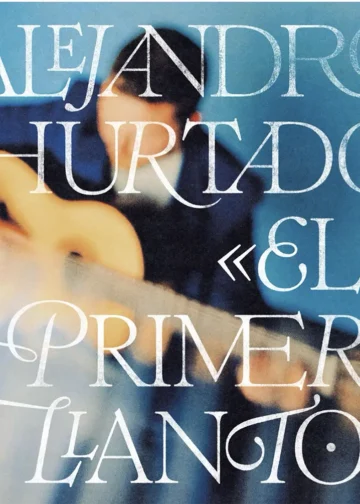

A reflection on the legendary singer a quarter century after his passing

On July 2nd, 1992, everyone was feeling optimistic. Summer had just barely begun and we were looking forward to its delights…paella, fried fish and sangría on the beach, and the numerous cante festivals that were still highly relevant. The Olympics of ’92 were about to begin in Barcelona after more than seven years of preparation, but on the midday news, they briefly stopped talking about that mega event to read a news item that shook flamenco to its core, and left us without the well-worn honeyed voice of one of the most charismatic figures of flamenco singing of all time.

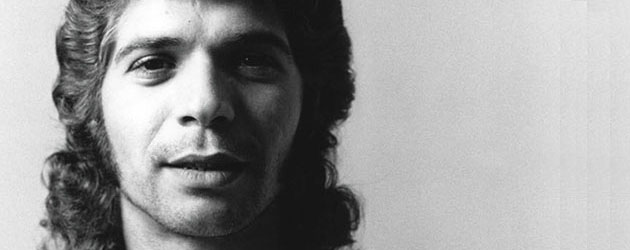

Even knowing he was gravely ill, it was something you didn’t expect. José Monje Cruz was only 41, and he represented for his generation the rebirth of a genre that had begun to seem overly exclusive and elitist, something old people do. Before Camarón, singers didn’t wear hippie clothes or get tattoos or wear rings with occult symbols. These were heady times of dramatic social changes throughout the world, and Spain was struggling to keep up.

“He’s a boy with the voice of an old man” some said, and others answered, “yes, but…is it flamenco?”

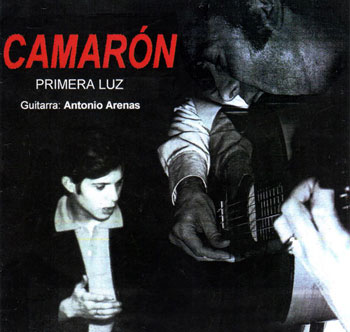

People say all kinds of things… “La Leyenda del Tiempo” was the beginning of the revolution? Not at all. Anyone who was in flamenco before Camarón was in circulation, remembers his surprising arrival to the recording market. There had been earlier lesser recordings that few people knew about, but when “Al Verte las Flores Lloran” came out in 1969/70…well, it’s hard to describe the impact. Now, those early recordings seem thoroughly conventional in every way…in any case, it was the guitar of Paco de Lucía that was breaking molds. But what everyone was talking about wherever flamenco fans gathered and cante was spoken of, the question hanging in the air, and which was obsessively debated was: ¿is Camarón flamenco?

That “canastero” way of bending the notes had little to do with Mairena, Caracol, Terremoto and other big flamenco stars of the era. “He’s a boy with the voice of an old man” some said, and others answered, “yes, but…is it flamenco?” Opinion was divided, but not for long. The boy’s irresistible way of singing, supported by the brilliant freshness of Paco’s guitar, sparked nearly everyone’s imagination, and the first prize of the Festival de Cante Jondo of Mairena de Alcor, which meant approval from the maestro Antonio Mairena himself, consolidated his place as a young star on the rise.

By 1971, everyone in flamenco was talking about Camarón. His charisma, despite being a shy young man of a few words, and his artistic personality would spawn a multitude of imitators…and still today people are born who would follow his path, because it’s a sound that continues to fascinate.

I remember the day I saw the future of flamenco. Loud, clear and unmistakably. It was 1976. I went into the Corte Inglés in Seville’s Plaza del Duque, and as I’d done countless times before, headed for the record section. I glanced casually upwards and saw a sort of large billboard that was the list of the week’s top ten songs. Didn’t bother to read it, I was only interested in flamenco…but hold on…what’s that about “Rosa María” by Camarón de la Isla? For heaven’s sake, they confused the list of national best-sellers with local releases, ha. It’s true that the song was playing in all the bars and cafeterias, fairs and discotheques, it was blasting out of car radios and people were humming its catchy chorus: “Rosa María, Rosa María, si tu me quisieras, qué feliz sería”. Nevertheless, it was just a little ditty sung to the compás of tangos and accompanied by Paco’s guitar. I tipped off the salesgirl that they’d made a little mistake and put a flamenco singer on the nation’s list of best sellers. She went to check, and soon returned. No, there was no mistake. Contemporary flamenco had for once and for all invaded the pop market and thus was inaugurated its reign. There would be no turning back.

People waited for him at the stage door so he could lay hands on their children, or just to catch a glimpse of the young demigod.

I remember the mega concerts later on when Camarón would draw the gypsy community of Madrid and from further afield. One in particular, at the Madrid frontón, a sports arena…large families with drink coolers and picnic baskets, much shouting and confusion, the intense flow of emotion, non-stop cheers of admiration, even tears. People waited for him at the stage door so he could lay hands on their children, or just to catch a glimpse of the young demigod. At the gypsy pilgrimage to Fregenal de la Sierra, I remember the singer’s likeness adorned napkins and plastic cups used to serve food and refreshments along the route, and people wore kitschy souvenir medals with Camarón’s likeness.

And I remember simple things too…like how he would often come down to the fiestas in Utrera, often just playing guitar for the everyone else. Early in the day word would go round, “José is coming tonight!”, but in Utrera he was treated in a natural way, as the friend he indeed was, especially close to Gaspar de Utrera, Cuchara and Miguel Vargas “Bambino”.

Later on would come “La Leyenda del Tiempo”, and the myth circulates that flamenco fans returned the recording to the shops saying it wasn’t flamenco. As if any of us of that era had money to buy the original record! But everyone had a copy thanks to the ubiquitous double deck cassettes which made it easy to pause the recording process in order to jump past things we weren’t interested in, and resume when there was cante. We knew Camarón had to make concessions, and didn’t hold it against him. You don’t hold anything against a god.

The rise and fall of a legend. The retina holds the last images of that concert in Málaga with Tomatito. Camarón with the dark red jacket, sleeves rolled up…ill and emaciated, barely reaching the high notes but trying all the same, not giving up for one second.

In December of this year 2017, José Monje Cruz, “Camarón de la Isla” would have been 67, still a propitious age for a creative flamenco singer. It’s impossible to know what he might have gone on to contribute, but like people say: he sings better every day.

Descubre más desde Revista DeFlamenco.com

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.