Interview: Pablo San Nicasio Ramos

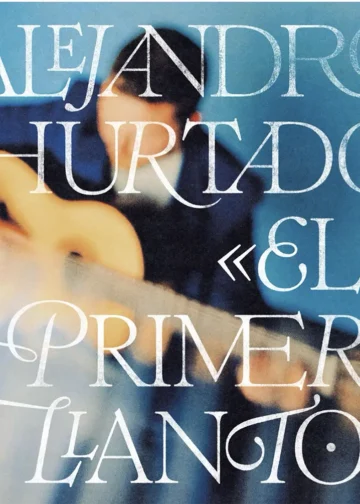

«The guitar, it must be said, is an instrument of accompaniment»

|

I’d always thought José Antonio Rodríguez was been a direct disciple of Manolo Sanlúcar. His concept of flamenco, his flair for teaching, his academic knowledge of music and his age all seemed to add up in my mind to the same route as Riqueni, Amigo and company. But no, as fate would have it, although the coincidences were and continue to be there, this Córdoba guitarist has joined forces with the maestro outside the classroom, not in. Just a few decades were enough to bring them together for this work “Anartista”, which he talked about in an hour of conversation. I’ve lost count of how many records you’ve made, because some aren’t available any more, others show up sporadically, others not at all… Calahorra and Callejón de las Flores were released in vinyl. Fantasía is the CD versión of Callejón de las Flores, it’s the same record…meaning, this is my sixth recording. And generoursy long and varied, eclectic, with pop themes…and what about that unusual title?…because I don’t really get it. It’s a long record, and some things even got left out. The initial approach was it was going to be a guitar record, there are two or three pieces that are primarily guitar. The farruca, the toná…that’s where I started. The title was also one of the first things I thought of. And it’s a question of personal anarchy. I don’t try to investigate or discover anything. What I’ve done is incorporate the flamenco guitar in other vital and artistic circumstances of my own, whether in the form of other artists or styles. Yes, because only Alejandro Sanz is missing. And he’s not on the record because of the iron-clad contract he has with his record company. The rest are voices I have a personal attachment with. People from the world of pop, others from rock, some from flamenco of course. It’s the recording of a flamenco guitarist showing how natural his instrument is in other styles. And all the interpreters I thought of are doing their own thing, each with a piece. In that sense, it’s very calculated. And I had a year and a half to do it, which is why it’s very polished. Since the record “Córdoba en el Tiempo”, it’s been five years. What happened right after that? When I finished that, I had nothing else in mind. After bringing out new work, I don’t like to think about creating anything different. So where does the anarchy come in? I meant personal anarchy, which is how I felt the urge to be in my own existence. I don’t bow down to flamenco in this case, but rather to my own wishes to evoke my biography. I don’t know how the next record will come out, for all I know it’ll be a fantasy for guitar and trumpet [laughter]…I don’t know. What did you base the toná on? On siguiriyas? It must be tricky to approach doing guitar in a style that doesn’t have guitar. I mostly went by what I could say in what tonality and how. The rhythm didn’t matter, I was looking more for what would help the cante of toná. I took things from the tonás of Morente, Gallina, Fosforito, Poveda…classic interpretations. And one in particular that I was able to hear of Fernanda de Utrera, that I don’t know if it was ever commercially released, but it’s absolutely wonderful. In tonás the hard part is maintaining the sustained notes, to make them last in time and not fade away. And how did you manage to convince Manolo Sanlúcar to do a rumba with you? Quite honestly I had misgivings about approaching him, because of the nature of the work. But I told him, and I hardly mentioned the more flamenco pieces. He said: “look, just what do you want?…that we play a piece together?” And he proposed doing something in the mixolydian scale, which is, as you know, something he’s been working on a long time. Of course, that might sounded a little cut and dry, so between the two of us we decided it would be more accessible if we did it via rumba. How is the maestro these days? Fine…he’s working on an encyclopedia of flamenco guitar. I play four pieces on it, in addition to this rumba. And there are many other important artists. It’s going to be a master work. Earlier you said this record had commercial elements. What I meant was there are styles, clearly, that are much more commercial than flamenco. Don’t get me wrong, I didn’t make this record with that objective in mind. I did it because I was interested in voices of friends of mine, such as Antonio Orozco, Mafalda Amauth, David Demaría, etc. Mafalda is a real wonder, she doesn’t seem Portuguese unless she wants to. Hers is a prodigious voice from Portugal. She speaks five languages perfectly and is a revelation. She sings in Portuguese because I asked her to, otherwise you’d think she’s from Sevilla. But it sounds more like Piazzolla than fado. Yes, because what I was looking for in Mafalda was her expressiveness. I tried to unite flamenco, fado and especially Piazzolla’s urban tango. Whom you actually met… Yes, in Liege, at a festival I also shared with Leo Brouwer, and the Paraguayan guitarist Baltasar Benítez…what a treat. I actually recorded Piazzolla’s rehearsals, but don’t ask me where the recordings are. Just like I recorded things of Chano Lobato when he came to my house and I lost them… Getting back to “Anartista”, what’s your relationship with these pop musicians? I met Antonio Orozco when I was working with Malú. His parents are from Osuna, and have a lot of respect for flamenco. He often works with Arcángel. I started playing for him in a benefit show in Seville, and I realized his voice is perfect according to my way of thinking, because flamenco guitar goes perfectly with his from of expression, whatever the style. In the case of David de María, who’s from Jerez and lives in Chiclana, this is someone else who is very respectful of flamenco. I have emails from all of them in which they say what an honor it was to have collaborated on a flamenco record. But that wasn’t the idea, I wanted to create something for them, in their own style, and with my guitar sounding flamenco, but they were feeling good doing their own thing. “Now there are fewer opportunities again, and I’m pessimistic. There are people who play exceptionally well and who are very prepared, but they’ll never make a recording even though they compose fabulous original music. And that’s sad”. The case of Santiago Auserón is somewhat more exotic so to speak. He’s more of a rock musician, and yes, his name is probably the one that raises the most eyebrows of all the guest artists. When I was small, I used to mostly listen to my father’s records…Fosforito, Paco de Lucía, Manolo Sanlúcar…but also to my brother’s…things like Radio Futura, Bob Dylan…and naturally, among the things I liked and had a special soft spot for were singers with personality, and Santiago Auserón was always one of my favorites, I love him. We worked together in a gig for the Taller de Músics in Barcelona, and it was a wonderful experience. It was hard getting him to participate in “Anartista” because he’s involved in finishing his studies for a degree in philosophy, and finishing writing a book…but he’s there all the same. And he’s incredible. The verse he sings is based on ideas from Maimonides, just to give you an idea. And his phrasing, his way of singing is total, because it was really difficult to do it like that, everyone in the studio said so. And why the song “Francisco Alegre”? I always use it to warm up, and to get the tone in the sound-checks. And I have it in a variety of ways, a thousand different variations. I don’t know why, but I’ve always liked it a lot. And I knew the voice it needed was Carmen’s, and she was very accessible. Carles Benavent is also there, and I love him. Your career as composer is very varied, and perhaps to understand all this it’s necessary to know who you hang out with and with whom you’ve worked. Yes, I have two concertos for guitar and orchestra which have been performed, but which I would like to record and yes, it’s like you say, they call me to compose and I’ve spent many years working with all kinds of styles. I give them all their importance and want it to show, which is the case on this recording. The last time we spoke I was composing for a classical guitar quartet, a piece of work commissioned by the group “Eos”. And they asked me to write a piece, in addition to playing things of Gismonti, Paco de Lucía… “You tell someone you’re a guitarist, and they ask you who you play for or what group you’re with. That’s what there is, and listen, it’s no big deal. Manolo Sanlúcar believes that what happened with “Caballo Negro” and “Entre Dos Aguas” isn’t going to happen again. Purely instrumental music making such a splash…that’s impossible now”. Then there’s your teaching facet. Yes, I still do master classes and courses abroad…we just returned from Switzerland and Russia. You see what there is there, and you realize nothing’s been done in flamenco. You have to start from zero. You tell the guitarists to play something Spanish, and they do “Cielito Lindo”. It’s normal for them to think that playing flamenco is playing with a certain passion, they don’t necessarily realize it’s a specific musical form with strict rules, they don’t process that, and you have to begin from square one with them. So it’s easy to see why they say they can’t distinguish a granaína from a malagueña…even Spanish folk music seems flamenco to them. So of course, that has to be explained, it’s not enough with the records they buy. And worse yet, they only have the latest of the latest. Of course it’s important to know what you’re playing. Well, there are plenty of people who play flamenco by inertia, just for fun, without knowing where the things they like come from or what they are. I can just imagine your maestro Manolo Sanlúcar thinking exactly the same thing, and feeling frustrated. Of course, you can’t put a siguiriya with a happy verse for example. But listen, everyone thinks I was one of Manolo’s students, but unfortunately it’s not so…I wish! We’ve played together a lot, so that’s why everyone thinks so, but I never had the honor. In his times with Riqueni and Vicente, I was also around doing concerts, at another stage of my life, and unfortunately we didn’t do any classes. You were one of the prodigies…does it have any advantages in the long run? That was the only way back then, you had to go to contests and win them. To play solo on stage, you had to go through that. Now there are fewer opportunities again, and I’m pessimistic. There are people who play exceptionally well and who are very prepared, but they’ll never make a recording even though they compose fabulous original music. And that’s sad. In the end, the guitar is once again an instrument for accompaniment, like Manolo Sanlúcar himself says. That could hurt a lot of guitarists’ feelings. That’s what this record is. The guitar was always accompaniment, and even more so for the general public. You tell someone you’re a guitarist, and they ask you who you play for or what group you’re with. That’s what there is, and listen, it’s no big deal. Manolo Sanlúcar believes that what happened with “Caballo Negro” and “Entre Dos Aguas” isn’t going to happen again. Purely instrumental music making such a splash…that’s impossible now. At the time it was a novelty, a historical turning-point. Call any radio station now and you’ll find out. Thanks to this record, many people came to know me and got into flamenco guitar. They hadn’t even known there was such a thing.

|

Descubre más desde Revista DeFlamenco.com

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.