Sara Arguijo

A demanding, meticulous perfectionist and passionate defender of creative freedom, Ernestina Van de Noort looks to the future with absolute confidence in what the new generation of artists is bringing, and with the challenge of continuing to lay out the universality of the art she loves, and its capacity to dialogue with other musical forms.

“Here in Holland, there aren’t enough flamenco fans to fill theaters, we’ve won people over with the shows”

We’re talking via Skype with all the associated hustle-bustle of the impending opening in just a few days, of the sixth edition of the Flamenco Biennale which, for 17 days (from January 13th to 29th), will fill the main venues of eight cities in the Netherlands with contemporary avant-garde flamenco. But also with the peace of mind that comes from a decade of managing a festival that has been able to find its place as one of the most important cultural events of Northern Europe, with the inevitable aspirations that come from believing in what one does.

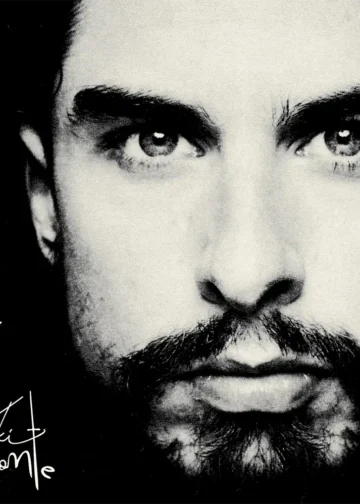

Photo: Ernestina van de Noort by Amaury Miller

Program of the 6th Flamenco Biennale VI

-At what point is the Bienal right now?

We can say that as of now, it’s a festival valued nationally and internationally. We’ve expanded to eight cites, and grown in comparison to the last edition, which was already a huge success. When we started out, there were so many municipal theaters, they were reluctant to program anything that sounded like flamenco. Now however, they’re lining up to join in. I’m proud of having managed to carve out an ever-bigger space for the Bienal in the Dutch cultural landscape, and the recognition of the general public, the press and institutions who have given their support. We’ve entered into the plan of national arts, of the Dutch Fund of performing arts, who heartily support our artistic focus on the renovation of the art-form. Thanks to this, we have a bit more leeway. You have to remember that flamenco is an adopted art in Holland, we feel it, but it’s not ours, and to receive support for a foreign art is quite an achievement, although the help is structural and not economic.

-One of your objectives has been to show flamenco’s capacity for dialogue, and to bring to the Dutch people work that belies the cliché images of flamenco. Has your message gotten through?

-This has always been my ambition and objective, and I think we are achieving this. There has always been great interest in flamenco here, but that following was never enough to fill large theaters, as happened in 2015 with El Pele and Farruquito, where 1500 people came to listen to flamenco singing. My aim is to program tradition and experimentation to create an avid, curious audience that wants to delve into flamenco beyond the preconceived image. Anyone who comes to the Bienal knows they are going to find experimental dance, dialogues with other genres and home-grown flamenco, the “Nederflamenco”, which makes room for national talent, as is the case of guitarist Tino Van der Sman.

“Flamenco is not only universal through its music, but through its capacity to provoke emotion. And that’s what we most want in Europe”

-With that aim to dialogue, this 2017 edition is presenting two productions of its own.

– Yes, one of them is an alliance with the Bienal de Violonchelo. We’ve created a “Fantasía para violonchelo y flamenco” with Rocío Márquez, the Austrian Iranian star of the cello, Kian Soltan, and the Dutch Cuban Ella van Poucke, a Turkish kemençe Derya Türkan (whom I discovered with Rénaud García Fons in the previous bienal), and a Spanish multi-instrumentalist, Efrén López. It’s a musical dream come true for me, the mix of music and genres, my calling card for this Bienal, something I’ve always wanted to do since the beginning. And then, we have another creation with Sara Cano, a dancer whose artistic idiom is fascinating for me, and the Indian choreographer Kalpana Raghuraman. A contemporary encounter between flamenco, with “Sara A palo seco”, and the Indian dances of “Rebels’ Cross”, where you can also see the similarities between both idioms.

“There was a Dutch audience that rejected flamenco because they thought it was folklore, and thanks to the Bienal I’ve found a kind of flamenco that interests them”

Photo: Ernestina van de Noort by Amaury Miller

-Daring undertakings to which you’ve added Rocío Molina, Manuel Liñán, Isabel Bayón, Rocío Márquez. It sounds like a program that wouldn’t go over too well in Spain. Does flamenco need to become Europeanized?

“I have more freedom to program, and I make use of it. I’m not trapped by tradition like Jerez or Seville”

-Is that your “anti-polkadot” message?

-Well, I’ve always wanted to show people the possibilities of this art, but as far as I’m concerned – everyone take note after 12 years! – I love polkadots. In fact, I no longer need to send out the message here, because it’s no longer needed. I can now afford to program more traditional things, it’s been like a reverse process. I always allow plenty of room for flamenco singing, something other non-Spanish festival don’t normally do. This year for example, we have José Valencia with “En Directo” and, although Antonio Canales is guest artist, the singing takes center stage.

“My calling-card for this Bienal is the ‘Fantasía para Violonchelo y flamenco’, a musical dream come true”

-And during this time, has the perception of the Dutch public at large changed with regard to flamenco?

– Of course, audiences have evolved. When we started out, we programed three venues, one for contemporary music, another for jazz and another, the municipal theater, places which had never programed anything flamenco. Like Don Quixote, we tried to seek out new audiences who had no interest in flamenco, because they though it was folklore, but seeing the shows, they’ve become convinced that there are things they are indeed interested in. Nowadays, it’s a very diverse, inquisitive audience, that reflects the wide range of flamenco expression that we offer and which they find at the Bienal where there is a guarantee of high quality.

-How important are the parallel activities?

-From the beginning we’ve considered the educational role to be fundamental. We have two kinds of workshops, an official one at the Rotterdam Conservatory with Faustino Núñez, and others dedicated to amateurs in singing, dance, guitar and rhythm, like what Torombo and El Oruco are offering this year. We have creative laboratories and experimental workshops with the artists who can then present the results on stage. And since 2006 we also include master-classes in dance, this year to be conducted by Antonio Canales, these are moments when the general public can get down to basics in the flamenco kitchen and discover for themselves just how difficult this art is. We also have a very interesting concept, a sort of flamenco soup, a taste of flamenco, where the audience can feel, in a natural way, the flamenco atmosphere of sitting around a table under the direction of maestro Diego Carrasco. Then, to bring the Bienal into the street, we’ve organized the “Flamenco Pop-ups” so the artists can perform right in the vestibules of the theaters and public spaces with a portable flamenco stage. Without a doubt, all this favors the creation of an excellent atmosphere of camaraderie and exchange. Very gratifying.