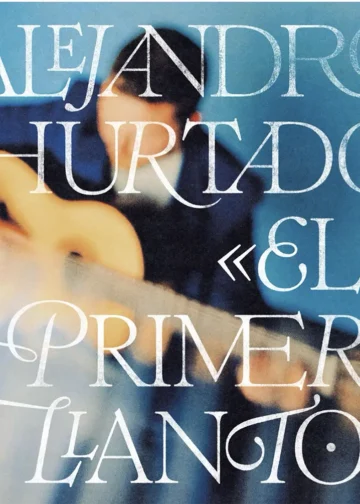

Interview: Silvia Cruz Lapeña

Photo: Rafael Manjavacas

He arrived in Barcelona at 19 encouraged by El Torombo, but at that time he had already been broken in playing for legendary singer Chocolate.

Against rolling cigarettes, and flamenco confusion

“It all began here.”

El Perla says this as he points toward the sea, to a promenade full of half-dressed tourists who seem to endure the city more than enjoy it. «It was here in this city I started out as an artist» explains El Perla gesturing towards the door of the Teatro Capitol, where he showed up with a man-bun, white trousers and a dark shirt. A guitarist's hands are important, which is why when he lifts a finger to indicate the path he followed after arriving in Barcelona, his porcelain finger-nails are so obvious. «A Chinese guy near my house does them for me. You can imagine how much my nails wear down with two shows daily». Those artificial claws are the only concession this gypsy guitarist permits himself, a man with a very clear idea of what flamenco is: «Each individual gives their special twist, but this art-form accepts little invention. It's a legacy we're failing to respect».

El Perla has that nickname for reasons you can imagine: «As a child, the family began to call me that because I was a bad boy, 'a pearl'». And the name stuck. I like it so much, I always stipulate it appear on programs just like that, without first and last names». He says he's never seen flamenco as a profession, but rather a way of life, and perhaps for that reason, even at home, he's known by his nickname. «My little girl calls me Papa Perla» he says, and he loves it.

When El Perla says «it all began here», he's not telling the whole story. He came to Barcelona at 19 thanks to El Torombo, but, at that time he had already been broken in playing for legendary singer Chocolate. Knowing the story of this 36-year-old guitarist, you get the impression he learned the job through a lot of hard work and fear. «When el Chocolate asked me to accompany him, I didn't want to, I wasn't prepared for that». He says something similar when he explains how he came into contact with the Farruco family. «One day El Moreno, father of my friend Farruquito, asked if I would go to America with them. In the end I went, but I was terrified to play for a family with that kind of power. That cost a lot of sweat and nerves until I could finally get through it». He describes all this with deliberate humor, and half-spoken phrases full of meaning.

The tablao, a home away from home

El Perla was born and raised in the Seville neighborhood of La Macarena, where he struggled in the beginning to learn the guitar, with no teacher, just by ear. But the fear is gone. «I don't teach because I'm still learning, I have a long ways to go. Nowadays anyone gives a master-class». He talks straight and pointedly. He doesn't believe in contests he says, but it annoys him that guitarists are awarded prizes when they've just begun their careers. It's not his only complaint, and although he doesn't speak with bitterness, he is very expressive in what he says. «Today's flamenco is like Sálvame Deluxe [popular TV program]. They take someone, they promote him and make him an instant star. Without having done anything. Flamenco is music that takes time to steep».

He feels today's flamenco is full of trendy practices that do it harm. «Nowadays, to be a modern flamenco, you have to roll your own cigarettes». For him, being flamenco is a way of life, a way of being, and of shining.

«I went to bed at six in the morning» he says during the interview. Then he jokes about artists' hours, after which you'd expect to hear about some wild fiesta. But the story is another: «When I get home after playing, I can't suddenly get down from the adrenaline. That's why I get into the studio, I go for a swim or I watch a documentary in order to relax». He's married to a singer, Eli de Santiago, who understands all this. «Sometimes when I'm rehearsing, my son's banging on the guitar in the next room, Eli is singing and my daughter is dancing…that's happiness».

El Perla chose to tell his life story over by the Ramblas promenade, in that confusion of people you cross paths with, like it or not. He describes himself as very reserved with regard to his private life, but on stage he's more open. Several hours later he'll demonstrate this at the Tablao de Carmen where he's been working four years, as long as other flamenco commitments allow him to do so.

Por soléa

Flamencos are different by daylight. At the Tablao de Carmen, located in that grand set-up known as Poble Espanyol, El Perla appears as he did in the morning, but in reverse: dark trousers, white shirt and loose hair. The artistic direction of a tablao he considers his home, is shared with dancer Manuel Jiménez «Bartolo». «I express myself here every day, and I put myself to the test. It's not easy to be fresh when you do two shows every day».

It's a summer afternoon, and there's still daylight when the first show begins. So much light doesn't feel right for flamenco. The people up on stage know it, they know there are verses and poses that are enhanced by the night. The performers do their job and provide background for the tourists' dinner, but it's the energy of the second show that highlights why so many people want to hear El Perla's guitar. Control and enjoyment. He directs the stage, follows the steps of Pepe de Pura, the story being told by La Tana and he lets her shawl sweep across his face, following the rhythm without skipping a beat. «I've never wanted to be a soloist, I like to accompany, I love accompanying a singer or dancer». This is borne out at the tablao, as well as in the many shows he's done this year. Most recently, accompanying El Yiyo in his Madrid debut for Suma Flamenca.

El Perla is in demand for his rhythm, his command of the tempos and knowledge of flamenco. He made a name for himself playing soleá: «Just think, as hard as it was for me in the beginning with that form. And now I've played soleá for La Farruca, it makes my hair stand on end».

Even singers from Jerez seek his services. «And they're a tough bunch, very chauvinist» says El Perla laughing. «But I'd like to be in some places where it's always the same people». He's not saying anything we don't all know, that promoters don't take chances, they always give the audience what they already know. But the person saying so in this case is one of the victims. «Artists call me directly, no agents involved, no promoters. And that in itself makes me feel good».

Flamenco without concessions

When the show is over, he comes to say goodbye. He's dressed in street clothes, and only the loose hair reveals he's just performed. «And that's how it goes every day» he says proudly. This man who has known and played with greats such as Juan del Gastor, has accompanied Bernarda and Fernanda de Utrera, Lola Flores in Seville parties that were common at the bar of Antonio el Cordobés, and who came of age at the legendary peña Torres Macarena. Along with José Maya, he mounted «Latente», a piece which includes «monsters» such as José Valencia, Rubio de Pruna and Juana la del Pipa. These are the kind of people El Perla directs with the music that flows from his fingers.

This is the same man who finishes playing at a tablao full of foreigners who have no idea who he is. He doesn't care, he learned discipline watching the rehearsals of Mario Maya, and something Farruco said to him is etched in his memory. «One day I asked him why he remained still after going off-stage. No one could see him, but he remained still, and in position. He answered: 'Because I see myself'». And he applied this all the time. That's why he acts the same, no matter who is listening, and wherever he is. In a tablao full of foreigners, at a private party, at the last Albuquerque festival or at Madison Square Garden. And he demands the same of his colleagues.

El Perla doesn't compete in contests, nor does he give classes, and although he says he still has a lot to learn, he knows that according to his age and walk of life, he is in a crucial moment when a little push is necessary and can make all the difference. He alternates large format shows with the tablaos of Barcelona, a city with too many foreigners and not enough support for flamenco. «A lot of people in Seville ask me what I'm doing here, and I tell them: 'I live my life'». He admits he'd like to be included in more shows in Spanish and foreign festivals, but he is also clear he'll make no concessions. «I'm well aware of the flamenco I defend, and also that in some places it's considered old-fashioned.».

He says this as he lights a cigarette. One of the pre-made type, not rolled by himself.

Descubre más desde Revista DeFlamenco.com

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.