Silvia Cruz

The Málaga guitarist presented his sixth recording, Picassares, at the Teatro de la Abadía on June 25th in Madrid's Suma Flamenca.

“The artists of my generation are once again looking back at classic flamenco references”

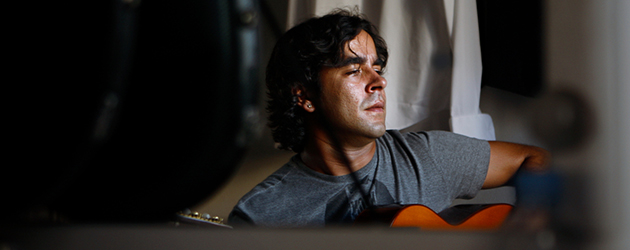

After years of accompanying the maestro Juanito Valderrama, the guitar of Daniel Casares has carried out such diverse tasks as accompanying the prodigious voice of Dulce Pontes, and commemorating the 75th anniversary of the bombing of Guernika via flamenco music. This man born in 1980, won the Bordón Minero in La Unión at the age of 17, but now he is more concerned with creating and performing than collecting prizes. He claims to feel respected within the world of flamenco, but acknowledges with certain resignation that 80% of his work is outside Spain. «It's not a complaint, simply the reality» he says laughing. With 25 years as a professional under his belt, he's found time to make five recordings. At Madrid's Suma Flamenca it is the sixth, Picassares, whose pieces made up the June 25th recital at the Teatro de la Abadía.

What does Picassares owe to «Guernika 75», your tribute to the painting by Pablo Ruiz Picasso which in turn paid tribute to the bombing of the Basque city?

I could be said that the work on the show led naturally to a recording that many flamenco fans had requested, and which I myself was very interested in doing. From the moment I began to understand Picasso's work, I was hooked and from that point on a good part of my work revolved around his paintings and his life. We did the show, and as it was well-received, we decided to document the work by way of a recording. There are some differences between the record and the live show, as well as some variation, but basically Picassares is a consequence of «Guernika 75».

You have collaborations such as that of Dulce Pontes. How did you choose who would accompany you on the record?

Dulce is on my record, as well as Lulo Pérez, Miguel Poveda doing a number of Luis Eduardo Aute as a bonus track, and the Israeli bass-player Adam Ben Ezra. These are people I feel at ease with, and with whom I've been collaborating a long time, and we share a similar artistic curiosity.

The Brazilian singer, composer and guitarist Toquinho was going to appear, but in the end the collaboration isn't going to be limited to sharing a piece. Tell us about that.

Well, what happened was that we recorded a piece, but a few days later his manager called because they liked the experience so much, they thought we ought to record an entire record, one on one. The idea is to record in autumn, with our two guitars and nothing else, and that's why we decided to reserve everything for that project.

After working with various record companies, even some multinationals, why did you decide to self-publish Picassares?

Because much of the time I felt that as the creator I put in a lot of work, loving care and time, and as soon as I handed over my creation for someone else to move, I lost contact, control and the protection I gave. That's why, and because I spoke to a lot of colleagues who recommended I do this, so this time we decided to self-publish in order to control the entire process and do everything in a more personal fashion.

And now that it's finished, what do you think?

'm pleased with the decision, and I think it's the best option for artists nowadays, something a lot of people agree with. No one better than yourself to know what needs to be done, the effort required and how to present it to others.

Lately you've been saying that artists are returning to classic flamenco. What do you mean, and why do you think it's happening?

When I say this, I'm talking about the guitar, but I also see it in singing and dancing. What I mean to say is, I notice an about-face, one step back in time as far as musical questions. It's as if we're saying: «Where the dickens are we going? Are we not losing the essence of why we're in this in the first place?» All of us who work in flamenco get involved because we liked to listen to Caracol or Bernarda, or because we admire Paco de Lucía or Niño Ricardo. And I'm convinced, because I can see it happening, that artists of my generation are once again looking back to the classics.

In your case, why is it happening?

I think it's normal. When you're 22, you start travelling and you meet people from other kinds of music, other cultures, and you feel the urge to adapt what you learn to your own language, which in my case is flamenco. This happened to me with Brazilian music, when I learned new harmonies I couldn't wait to put them into bulerías por soleá. But when you start digesting all that, and you come into contact with people like Dulce Pontes, or Toquinho, who are older and more experienced, they show you that each one has to defend his own musical language. Something quite different is a point of encounter, but you can't stop being who you are. This is something I've learned in recent years.

You've been in music for 25 years, you've obtained many prizes and worked with important people. Can you make a living from flamenco guitar in Spain, or do you feel you're not appreciated in your own country?

I'll tell you straight and clear: if I had to depend on what I make in Spain, I'd be in big trouble. In my case, seven or eight of every ten concerts I give each year, are abroad. On the other hand, I do feel appreciated here even though what fills out my calendar are the concerts outside of Spain.

Do you think that the fact of not coming from a family of musicians, of being the first in your family to devote yourself to this, has made it more difficult for you?

I'm not sure, because there are many exceptions to the rule. There are people from a family of musician who are very good, but who have a hard time because more is expected of them. But there are also others who are professionals because of a family line, and although I think they'd do us all a favor if they gave it up, they do very well. So it's not really clear whether being from a family line is beneficial or not.

You always say that a guitarist has to rehearse and practice many hours, and that you're the type to spend 12 or 14 hours a day with the instrument. Are you able to devote that same amount of time now that you're a father?

My daughter needs me 100% of the time, so it's clear my schedule has changed. But it's also true that my partner understands the demands of my work, and is very supportive and this allows me to keep studying and devoting many hours to the guitar.

How has being a father influenced your work?

I think it's made a positive difference. I don't sleep as much as I used to, I've spent many sleepless nights, I'm more tired than usual, but I've also discovered that all that fatigue hasn't been in vain: it's reflected in my work, in my sound, and I think it's been positive. I have no regrets; I recommend all artists to become parents.