Interview: Silvia Cruz Lapeña

Historic photos: Jesús Santos

Current photos: A. Bautista

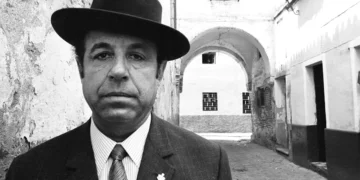

Mairena del Alcor to honor Calixto Sánchez on the 50th anniversary of winning his prize at the Certamen de Cante Jondo Antonio Mairena.

“Fortunately, art is not inherited”

At the other end of the telephone line, Calixto doesn't respond without first pulling a few notes out of the guitar which he happened to have in his hands when the phone rang. «Listen, that way of singing soleá is very difficult». He resorts to irony to explain what he's seen and lived through in this half-century, and when asked if he thinks he could win the contest today, he has no doubt that it would not happen: «I wouldn't compete. I went to the contest because I wagered a lunch with friends, and couldn't back down. But I was very green, and I was at college, so if it had caught me later on, with studies and a family to maintain, I wouldn't even have signed up».

He says he prepared the songs as if he were going to a math exam. «I took an old record of Pastora Pavón, chose the cartagenera and learned it by heart. I even knew the extraneous noise on the recording! I did the same thing with the malagueña of Mellizo which I took from Mairena». He talks about the difficultly of putting the songs to guitar, something he'd never done before. His apprenticeship was in his father's bar which received field-workers after two weeks working in the fields and who would come for a clean change of clothes and a glass of wine. «And from the local celebrations of Mairena del Alcor, from the great saeta singers who sang on the balconies during Holy Week. I didn't even pay attention to them, but that was the learning process that seeped into me little by little».

Maestro and singer

From that point on, he never let go of flamenco. He continued studying to be a teacher, but the world of flamenco had him hooked. «When I started out in this, Spain was a world of woe, small towns with a very closed mentality, and a tremendous lack of culture. With flamenco, I entered the artistic world, which felt like a society within a society, but more liberal, more permissive». He claims the new generation, such as that of Enrique de Melchor and Luis de Córdoba, had a better education, but the majority of performing artists were illiterate. «But it didn't matter because being among them was a great surprise: there was a kind of freedom that didn't even exist at the universities».

That freedom, and Sanchez' own character, allow him to speak openly. Even about the festival that honored him, and in which he has participated in other editions. «Lots of people ask me about the program, because some say it's weak, it could be better or whatever… The thing is, we have a big problem in my town: we had the extraordinary singer Antonio Mairena». He mentions the great artists who have passed through, from Bernardo el de los Lobitos, to la Niña de los Peines. «People here understand, but they can't accept that times have changed, and young people come who sing very well, like Rubio de Pruna, who's a fine singer, and mature, and they still complain. They don't get it that the people they admired are no longer alive».

Methodology and investigation

Calixto Sánchez is also critical of Mairena's most famous citizen: «He sought the truth of flamenco in oral tradition, because everyone looks for truth as he or she pleases, but in his quest, exhaustive investigation and methodology were missing». As far as this singer is concerned, what can't be heard, can't be judged. «When the children of Enrique el Mellizo say 'this is how my father sang', they're lying. You aren't your father. And if they don't think so, just ask Picasso, who had a ton of kids and none of them could paint. Fortunately, art is not inherited».

As far as the disagreements surrounding Antonio Mairena regarding gypsy singers versus non-gypsy, Sánchez is equally clear. «No one is pure here. And if you want to talk about the important names everyone mentions, like Silverio and Fresco el Tojo, they weren't gypsy. I wasn't gypsy, and I won the highest prize in my town. I wasn't even a follower of Mairena, because my path was another». For him, money is what's behind those never-ending debates. «The Mairena followers want to perpetuate a separation that doesn't exist. It's a way of eliminating the competition, but fortunately few of them remain». And he has no doubt that in Mairena the objective is good flamenco singing, beyond all labels.

A retiree glued to his guitar

Calixto can't say whether he's been retired three or four years, because his fingers go straight to the guitar at every moment, and he says he sings every day. He recalls his job as local schoolmaster alongside his wife, and how he taught the students fandangos, tanguillos de carnival and verdiales. «I was a pioneer in teaching music in the classroom» proudly says this man who carried on his work as school-teacher in parallel with his artistic career. «I performed on weekends and in summer. For me it was advantageous not to have learned by oral tradition, so I was able to focus my career. My base was academic and investigative, and that gave me a privileged position» openly states the man who has won all the flamenco singing prizes of Andalusia.

Calixto Sánchez laughs easily, and many of his comments are peppered with humor which is structured, but also the fruit of someone who sees things from a distance. At one point he becomes more serious: «Being on stage is very complicated. It's wonderful, and it opens the doors to a world I could never have imagined. But you also have to go to the depths». And when does that happen? «When you're singing but you can't get into it. When you're out of place and the audience notices. That's miserable». When asked if that has happened many times, he's concise: «Enough to have learned that in order to get up in front of an audience you have to be well-prepared. You can't just go up with four whiskeys to lose your shyness and make you think you're Don Antonio Chacon». And thus does Calixto get back to humor and to playing his guitar.

Descubre más desde Revista DeFlamenco.com

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.