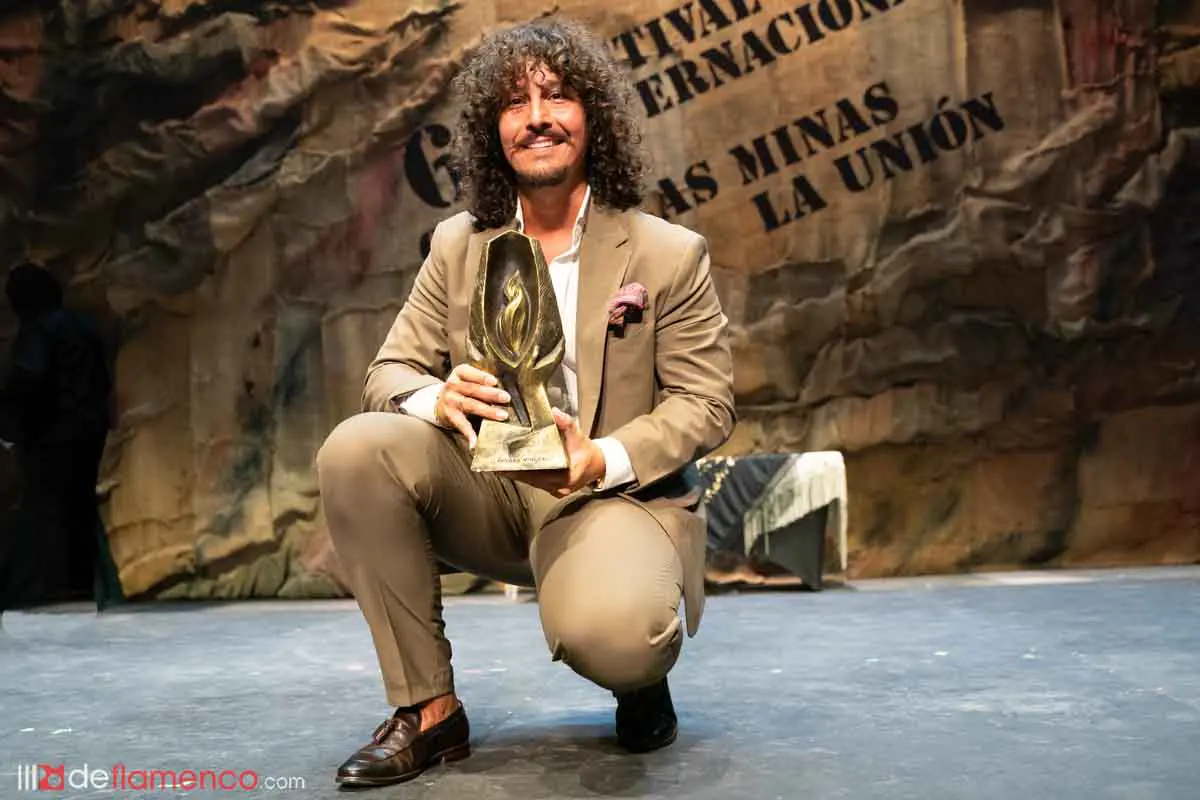

We took advantage of Jesús Corbacho’s visit to Madrid to chat with him at the Terraza de las Tablas about what it meant for him to win the 2024 Lámpara Minera, the emotions of that night, his career, the value of cante for dance, and his future projects.

Video of the full conversation:

Jesús, your dedication upon winning the 2024 Lámpara Minera was very emotional. What did that moment mean to you?

Just remembering it gives me goosebumps. Entering the competition was a tribute to my father, who passed away two months later. He took me everywhere, fought for my dreams… I knew it was my last chance to bring him that joy. When they announced my name, it was an explosion of emotions: the recognition of my career, the affection of the audience… And, above all, being able to say to my father, “I did it.”

How has your life and career changed after winning the award?

It opens doors. Before, even though I had been singing for 20 years for top flamenco dancers, many programmers would say, “Yes, he sings well… but for dance.” As if it were a flaw. When greats like Camarón or Morente started that way! Now, I get calls for recitals. Though [laughs] some still say, “Lámpara Minera, sure… but doesn’t he sing for dance?”

You speak passionately about cante for dance. Why do you think it’s undervalued?

It’s an absurd prejudice. Singing for dance requires rhythmic mastery, adaptability… Enrique el Extremeño is a beast on stage, and he’s a cantaor for dance! Flamenco was born that way: first the singing, then the dance follows. In fact, I always tell my students: “The guitar and dance should be aficionados of cante.”

How was the process of entering and preparing for the competition?

It was a personal decision, but I had key help from two maestros: Jeromo Segura and Miguel Poveda. Jeromo came to my house a thousand times; Miguel sent me voice notes correcting me… They taught me the secrets of mining cante. I’ve always been obsessed with listening to cante: in the car, at the gym… Even my kids say, “Dad, turn that off!” [laughs].

Your singing has a very personal touch. How would you define it?

Natural and real. I don’t know what dish I’m going to cook until I’m on stage. I have a peculiar voice – some people don’t like it – but I’d rather have that than be a copy. My thing is to tell a story with my singing, with honesty. Morente used to say, “The hardest singing is the one you struggle with the most.”

Have you ever been tempted to experiment with flamenco, like Rocío Márquez or El Mati?

I don’t rule it out! If I felt the need, I would do it. I’ve sung in shows where bicycles made sounds like seguiriyas [laughs]. But it has to come from within me, not just because it’s trendy. I admire Rocío and El Mati because their work is genuine. What I wouldn’t do is a project I don’t believe in, even if it paid well.

What projects do you have coming up?

I want to record a very special album: each track featuring someone important in my life. Artists like Miguel Poveda, El Extremeño… I dream of recording with Riqueni or Lole, I hope I can make it happen. Now, I’ll be performing at the Liceu in Barcelona for the Winners’ Gala – I never dreamed of singing there solo! – and I’m also continuing with El Choro, a crazy show where I dance, cycle… People leave happy, and flamenco is also about joy.

Offstage, you are a very family-oriented person, a devoted father.

My three children are my greatest gift. That’s why I entered the competition: to have more choices and be with them. This profession demands a lot – yesterday, my son played with the Andalusian national team, and I couldn’t go. We travel a lot, but sometimes all I see are airports and theaters. [Smiles] Now I’m also boxing with my brother; I had knee surgery, and they told me it was good for recovery.

Discover more from Revista DeFlamenco.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.